To provide beneficial palliative care for patients, Professor David Hui, MD, MSc, says oncologists just need one tip. Or rather TIP, which stands for timely, interdisciplinary, and personalized.

Dr. Hui, director of research in supportive and palliative care at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, recently discussed the integration of oncology care and palliative care at the 2022 Asia Conference on Lung Cancer.

“For patients with lung cancer, there are quite a few supportive care needs we need to think about, ranging from cancer-related symptoms, treatment side effects, co-morbidities, psychological distress, information needs, caregiver support, and end-of-life issues,” Dr. Hui said. “Whether you have curable cancer or incurable disease, these issues are prevalent.”

While palliative care initially focused on the issues closer to the end-of-life, Dr. Hui said supportive care needs are also present at the time of diagnosis lung cancer patients and throughout the patient’s disease course.

“Palliative care has evolved into supportive and palliative care, and we can serve patients earlier in the disease trajectory,” he said.

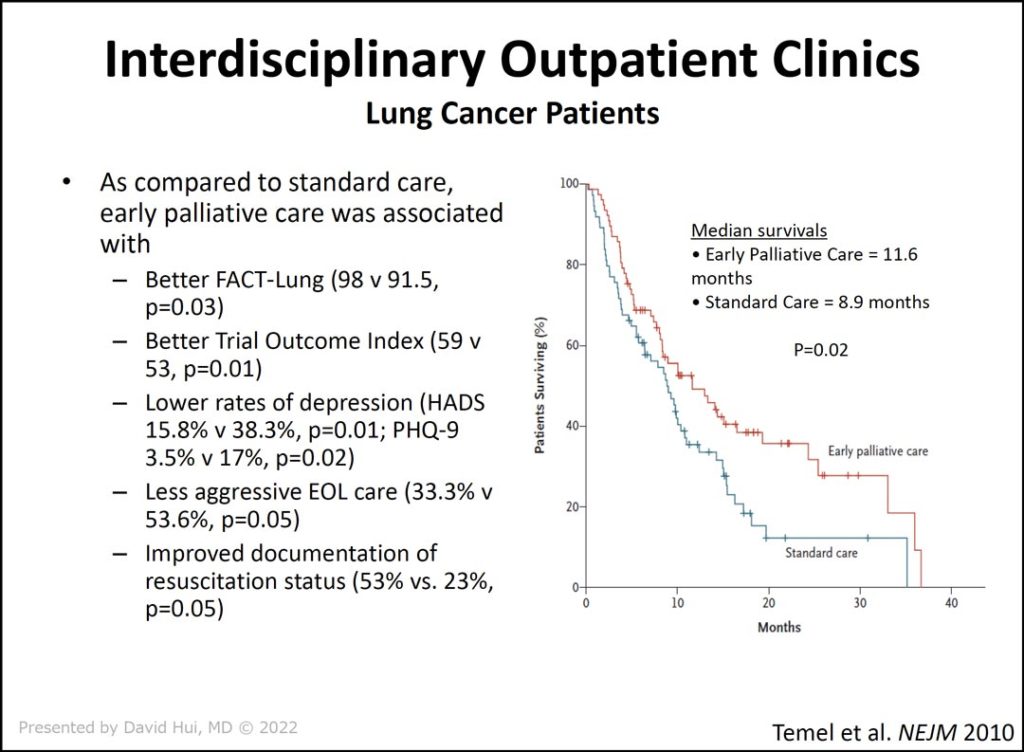

In outlining how to provide timely, interdisciplinary, and personalized care, Dr. Hui reviewed the evidence to support his TIP model of care. In the landmark trial by Temel et al (slide 1), patients were randomized to either early, integrated palliative care or to routine oncology care. The researchers found that timely palliative care improved quality of life, the patient’s mood, the quality of end-of-life care, and overall survival.

Compared to standard care, early palliative care was associated with:

- Lower rates of depression (HADS 15.8% v 38.3%, p=0.01; PHQ-9 3.5% v 17%, p=0.02)

- Less aggressive end-of-life care (33.3% v 53.6%, p=0.05)

- Improved documentation of resuscitation status (53% vs. 23%, p=0.05)

“With timely care, not only can we improve quality of life, but we may have some impact on how patients choose care at the end of their lives, leading to less aggressive end-of-life care,” Dr. Hui said.

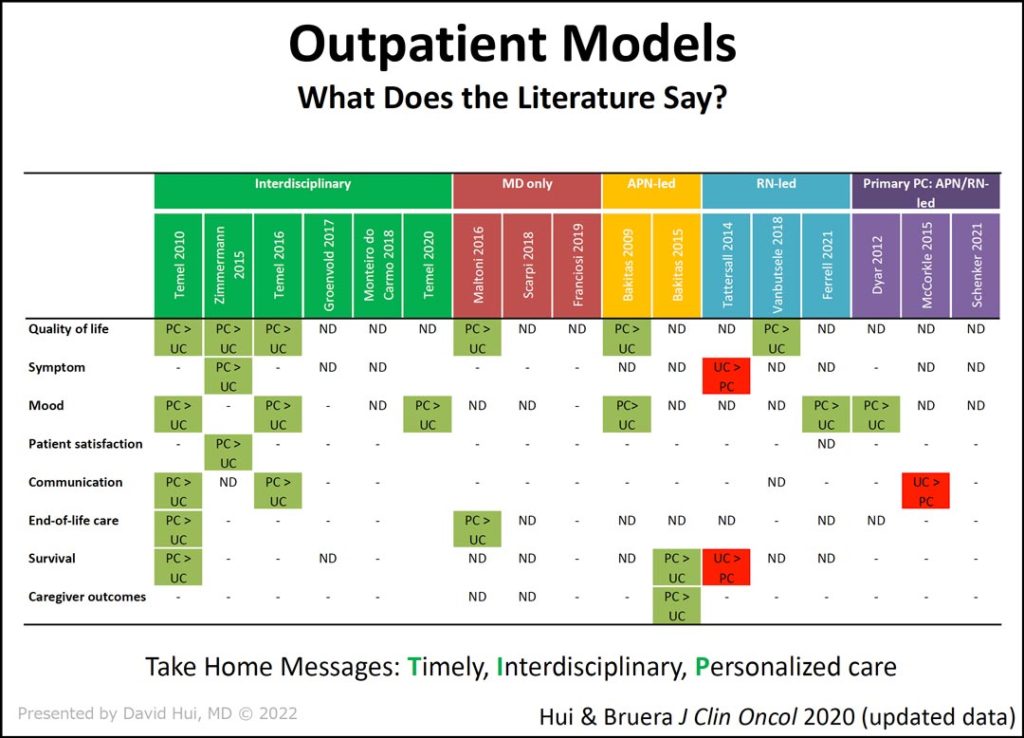

Since that time, multiple randomized controlled trials comparing outpatient palliative care to routine oncologic have been conducted (slide 2).

“As you can see, all of these studies have different models,” Dr. Hui said. “Some have interdisciplinary teams. Some of them are physicians only. Some of them are advanced nurse practitioner-led. Others are nurse-led models. And then there are the primary care-led models.”

The data show palliative care better than usual care in the studies marked in green, while studies marked in red found usual care to be better than palliative care. The other studies found no significant difference between palliative care and usual care.

“From this bird’s eye view, you can easily see the studies involving interdisciplinary palliative care teams have more of an impact on outcomes,” Dr. Hui said.

An interdisciplinary team can meet the informational, physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of a patient and present a unified message with common goals. An interdisciplinary model may include many specialists: nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, pharmacists, physicians, psychologists, volunteers, social workers, chaplains, and case managers.

Lastly, Dr. Hui discussed how to personalize supportive and palliative care for oncology patients.

“For me, the best form of palliative care is preventative care,” he said. “In supportive care, what we mean by preventative care is to recognize the patient has an advanced disease. The symptoms are going to be there. The dyspnea can get worse. It’s time to be proactive and start non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies, provide education and monitoring. Ultimately, we might be able to not only improve the patient’s quality of life but maybe this patient won’t have to go to the emergency room or ICU as a result.”

To do this in an oncology setting, education is key, Dr. Hui said. He reviewed the impact of the PEACE project in Japan, which conducted more than 1,000 workshops to train more than 10,000 physicians in palliative and supportive care.

“Participants in the training were more likely to refer patients and recognize the role of palliative care,” Dr. Hui said.

Following the project, an electronic survey of 923 members of Japan Lung Cancer Society showed PEACE participants (n=519) scored significantly better than non-participants (n=404) on a palliative care knowledge test as well as on the palliative care self-reported practice scale and the palliative care difficulties scale.

“It’s hard to get all oncologists to refer patients consistently, so some programmatic education is needed,” Dr. Hui said. It need not be difficult for oncologists to determine which patients need to be referred and when. In concluding his talk, Dr. Hui said routine patient screening coupled with defined referral criteria can be used to automatically trigger or flag patients for outpatient palliative care referral.