A middle-aged woman walks into the clinic using her right hand to hold her shirt away from her chest. “Even just my shirt brushing against my skin hurts,” she says with a grimace.

The patient is now 4 months out from a thoracoscopic right upper lobectomy for early-stage NSCLC. She continues to report sharp pain wrapping around her right side and radiating to her breast. She takes 300 mg of gabapentin twice daily but cannot tolerate an afternoon dose because she would otherwise be too tired to work. She has been unable to wear a bra since her surgery. Her pain was reasonably well controlled for the first 2 weeks after her operation, but as she recovered, the discomfort made its way into the forefront of her thoughts. Practitioners who work in thoracic surgery observe this scenario far too frequently.

Post-operative neuropathy is a frequent complaint in our thoracic surgery practice. Classically, this condition has been called post-thoracotomy pain syndrome (PTPS) and is a possible long-term complication following both thoracotomy and thoracoscopic incisions. These types of incisions mark the top two causes of both acute and chronic pain from elective surgery.1

Chronic post-surgical pain is defined as pain that persists or increases beyond 3 months after the surgical procedure.2

The etiology of this pain is often multifactorial. Some potential contributing factors include incision, retraction, resection, rib fracture, disruption of costovertebral joints, intercostal nerve injury, and pleural irritation from chest tubes or intraoperative insult.3

A meta-analysis from the Journal of Pain showed that the incidence of chronic neuropathy following thoracotomy at 3 and 6 months was 57% and 47%, respectively.4

Poorly controlled pain in the immediate post-operative period can lead to some well-documented complications, including pneumonia and atelectasis. Moderate and severe post-operative pain also correlates with increased rates of chronic pain.3

,5

,6

One study showed that aggressive post-operative epidural analgesia seemed to reduce the incidence of post-thoracotomy pain 1 year after surgery from 50% down to 21%.7

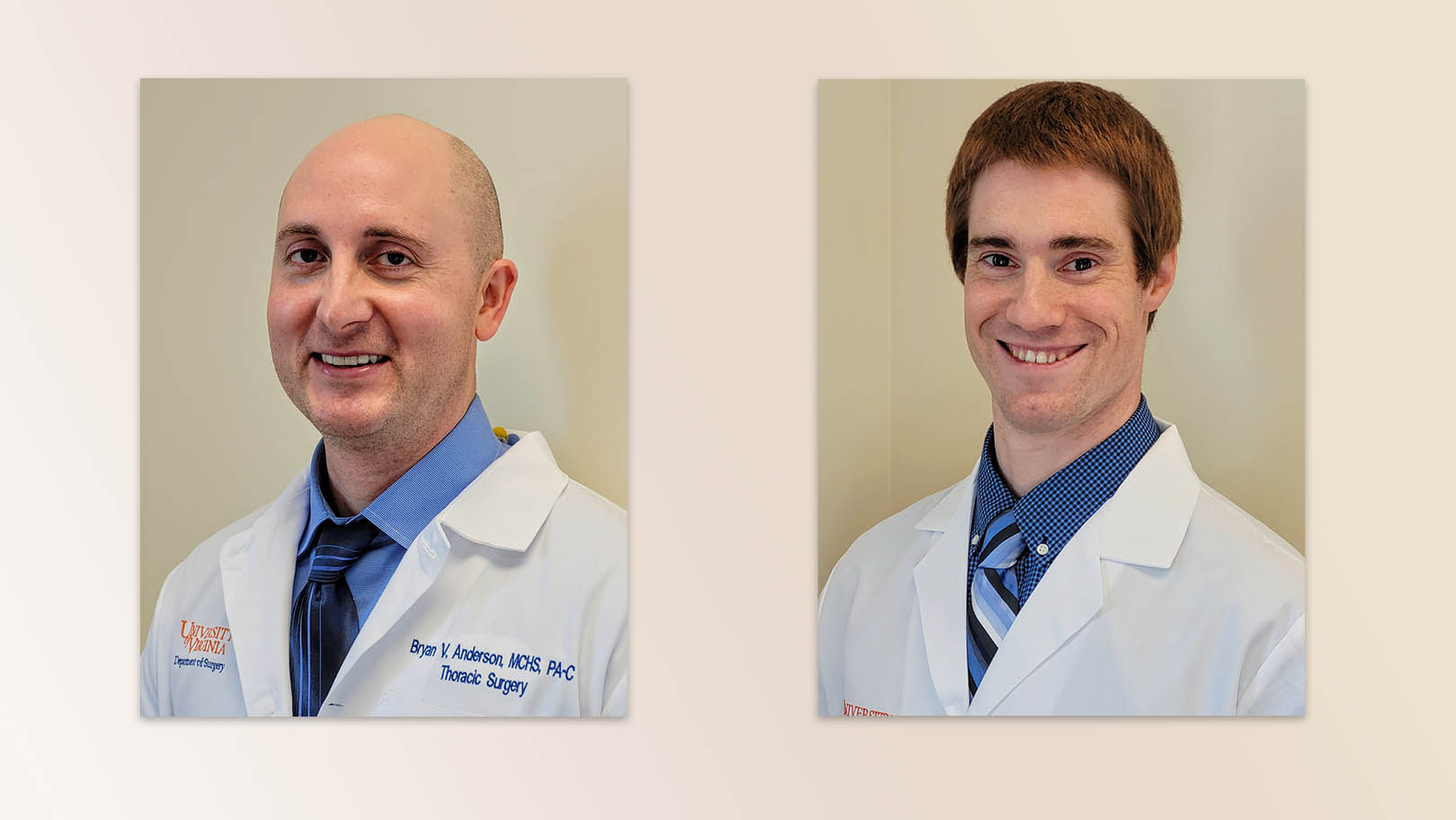

For the past few years, we have taken many steps to improve acute pain control while at the same time minimizing opioid use in the perioperative period. At our institution, the University of Virginia (UVA), this effort has taken the form of a thoracic Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) program.

The main goal of ERAS is to assist in lessening the physiologic and psychological stress of patients undergoing thoracic surgery through standardization of best practices and holistic pre- and post-operative patient education. A key component of ERAS is the focus on opioid-sparing pain management.8

Just prior to surgery, we routinely administer oral acetaminophen, gabapentin, and celecoxib. Intraoperatively, regional nerve blockade with liposomal bupivacaine is an intrinsic part of our pain-management strategy. We have had great success with regional nerve blockade so that epidural catheters are now only placed in more extensive surgeries in which pain is expected to be severe. Saline-diluted liposomal bupivacaine is injected percutaneously or internally into multiple intercostal spaces above and below the ports of entry.9

This injection can provide nerve blockade for up to 96 hours after injection, with median time to resolution around 48 hours.10

Following discharge, a good portion of our patients’ pain-control complaints can be addressed through re-education and ensuring appropriate timing and dosing of discharge medications. Often, patients need reassurance that what they are feeling is expected following their surgery.

Following discharge from the hospital, we attempt to limit our opioid prescriptions by using a non–opioid-containing regimen that includes alternating acetaminophen and ibuprofen every 4 hours, along with gabapentin every 8 hours. The typical dose ranges used are 650-1000 mg of acetaminophen three times daily, 400-600 mg of ibuprofen three times daily, and 100-300 mg of gabapentin three times daily. Studies have shown that 1800-3600 mg/day of gabapentin is effective and well-tolerated in the treatment of adults with neuropathic pain.11

However, in July 2019, gabapentin was deemed a Schedule V medication in Virginia, and later that year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a report warning about respiratory suppression in patients who received central nervous system depressants including gabapentin and pregabalin. For this reason, we tend to start gabapentin at a lower dose and titrate upward as tolerated.

Studies have shown that the rate and severity of PTPS usually decreases over time.12

If our medication titration efforts prove unsuccessful, our next step is to refer the patient to the chronic pain clinic. Our colleagues in pain management optimize the medication regimen with further dosage adjustments or begin alternative drugs such as pregabalin and duloxetine. For patients with severe neuropathic pain, we request consideration for intercostal nerve blockade. These nerve blocks typically consist of a local injection of anesthetic along with a steroid adjunct. Data suggest that although these methods often provide some measure of pain relief, it typically only lasts for a few weeks to 2 months.13

The pain clinic at UVA uses bupivacaine for at least one test block; if that provides relief, a steroid is added to extend the duration of effect. If a patient gets a month or less of relief with the steroid adjunct, then clonidine is sometimes added to further extend the duration of anesthesia. Neurolysis with alcohol is not commonly performed at UVA but is reported in literature. Unfortunately, there is not an extensive amount of high-quality data on the overall efficacy of nerve blocks to treat PTPS, and randomized control trials are needed.

Although we have made great strides in post-operative pain management following thoracic surgery, there remains room for improvement. We continue to strive to provide the best care for these patients, who are often already dealing with the stress surrounding their underlying diagnoses of thoracic malignancy, interstitial lung disease, or another condition. It is our hope that through continued research, patient education, and early recognition of poorly controlled pain, we can continue the positive trend of improved patient care and work to minimize the development of chronic pain.

- 1. 1. Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera D. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:1251.

- 2. Schug SA, Lavand’homme P, Barke A, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain. PAIN. 2019;160(1):45-52.

- 3. a. b. 3. Ochroch EA, Gottschalk A. Impact of acute pain and its management for thoracic surgical patients. Thorac Surg Clin. 2005;15:105-121.

- 4. Bayman EO, Brennan TJ. Incidence and severity of chronic pain at 3 and 6 months after thoracotomy: meta-analysis. J Pain. 2014;15(9):887-897.

- 5. Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Chronic pain as an outcome of surgery. A review of predictive factors. Anesthesiology. 2000;93(4):1123-33.

- 6. Katz J, Jackson M, Kavanagh BP, Sandler AN. Acute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy pain. Clin J Pain. 1996;12(1):50-5.

- 7. Ochroch EA, Gottschalk A, Augostides J, et al. Long-term pain and activity during recovery from major thoracotomy using thoracic epidural analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(5):1234–44.

- 8. Haywood N, Nickel I, Zhang A, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Thoracic Surgery. Thorac Surg Clin. 2020;30(3):259-267.

- 9. Martin LW, Mehran RJ. Intercostal nerve blockade for thoracic surgery with liposomal bupivacaine: the devil is in the details. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(9):S1202-S1205.

- 10. Manson WC, Blank RS, Martin LW, et al. An observational study of the pharmacokinetics of surgeon-performed intercostal nerve blockade with liposomal bupivacaine for posterior-lateral thoracotomy analgesia. Anesth Analg. Aug 20, 2020. [Epub ahead of print].

- 11. Backonja M, Glanzman RL. Gabapentin dosing for neuropathic pain: evidence from randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2003;25(1):81-104.

- 12. Kinney MA, Hooten MW, Cassivi SD, et al. Chronic postthoracotomy pain and health-related quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93(4):1242–1247.

- 13. Gulati A, Shah R, Puttanniah V, Hung JC, Malhotra V. A retrospective review and treatment paradigm of interventional therapies for patients suffering from intractable thoracic chest wall pain in the oncologic population. Pain Med. 2015;16(4):802–810.