Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world in terms of land area, and it ranks among the 15 largest countries by economy. However, Brazil is also a country of significant social inequality.

Under Brazil’s public health system, by definition, all citizens have the same right of access. However, more than 50% of the country’s healthcare resources are allocated to private systems, which serve less than 20% of the population.1,2

The main cause of death among non-communicable diseases in Brazil continues to be cardiovascular disease, but cancer is increasingly becoming the leading cause of death in cities in the south and southeast, which are considered more economically developed and generally have greater access to healthcare.3

Since the 1980s, Brazil has adopted an active policy to combat smoking and has seen a marked relative reduction, with the prevalence of smoking falling from more than 35% to about 10%.4 Still, with a total population of more than 210 million, the number of people at increased risk for lung cancer in Brazil is vast.

LATAM Workshop

Learn more during the LATAM Workshop. Ricardo Sales dos Santos, MD, PhD, will discuss the challenges of implementing lung cancer screening in Latin countries.

- Time: 15:00-16:30 CEST

- Date: Saturday, August 6

- Location: Lehar 2

Given Brazil’s large population and land area, the promotion of lung cancer screening here faces unique challenges. When it comes to public policy, initiatives need to offer access to populations that often have suboptimal access to essential goods, such as basic sanitation, clean water, maternity care, and childcare as well.

Since 2010, cancer screening and early detection initiatives—designed as research projects by specialists in institutions in several Brazilian states—have been implemented and their results published in the national and international literature.5,6,7 In 2016, the results of the First Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT1), which had 790 participants, yielded a prevalence of lung cancer similar to international studies (1.5%) in an area still considered endemic for granulomatous disease, especially tuberculosis. The BRELT1 study led to the creation of several screening centers, actively contributing to start performing lung cancer screening in Brazil.6

In 2022, five institutions in three Brazilian states gathered data from 3,819 individuals undergoing low-dose CT (LDCT), obtaining a higher lung cancer prevalence (2%) with the same biopsy rates recorded in the previous study (3.5%).7 This study, called BRELT2, concluded that it is possible to obtain satisfactory results with screening in real life in both the private and public health systems in Brazil.

Based on these findings, the first structured consensus on lung cancer screening in Brazil is being prepared. This initiative is joint effort by the Brazilian Medical Association (AMB) and several medical specialty societies, including of the Brazilian Society of Thoracic Surgery (SBCT), the Brazilian Society of Pulmonology and Tisiology (SBPT), and the Brazilian College of Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging (CBR). The initiative aims to influence and collaborate with public policy makers on this topic at national and regional levels.

Another effort, the ProPulmão initiative, has brought together specialists in regional meetings on lung cancer screening since 2018 and played host to the 41st meeting of the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP) in 2019. Support from IASLC made it possible to execute the first such meeting in South America after 20 years of existence of the I-ELCAP.

The ProPulmão group, which is based out of the Manufacturing and Technology Integrated Campus (SENAI-CIMATEC) University Center in the state of Bahia, recently launched a project to build a mobile unit for lung cancer screening in the northeast region of Brazil. SENAI-CIMATEC has received support from the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation for the project, and the group will soon begin to perform 3,000 LDCT scans in smaller cities in regions far from the bigger cities of Northeast Brazil. In addition, other institutional projects continue to progress in the states of São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, and Pernambuco.

Available data indicate that adoption of lung cancer screening is still low. One recent study using data for 10 US states found that 14.4% of people eligible for lung cancer screening (based on 2013 USPSTF criteria) had been screened in the prior 12 months.6 Certainly, in Brazil the rates are even lower.

Increasing lung cancer screening discussions and offering screening to eligible individuals who express an openness to it is a key step to realizing the potential benefit of lung cancer screening. The first step of increasing medical knowledge of lung cancer screening benefits has begun, but a huge effort is still needed in the public health system to include lung cancer screening in annual health checks.

In addition, from a radiologic point of view, standardized reporting is needed. To minimize the uncertainty and variation about the evaluation and management of lung nodules and to standardize the reporting of LDCT results, the American College of Radiology developed the Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System (Lung-RADS) and endorses its use in lung cancer screening.9 Lung-RADS provides guidance to clinicians regarding which findings are suspicious for cancer and the suggested management of lung nodules detected on LDCT. Data suggest that the use of Lung-RADS may decrease the rate of false-positive results in lung cancer screening.8

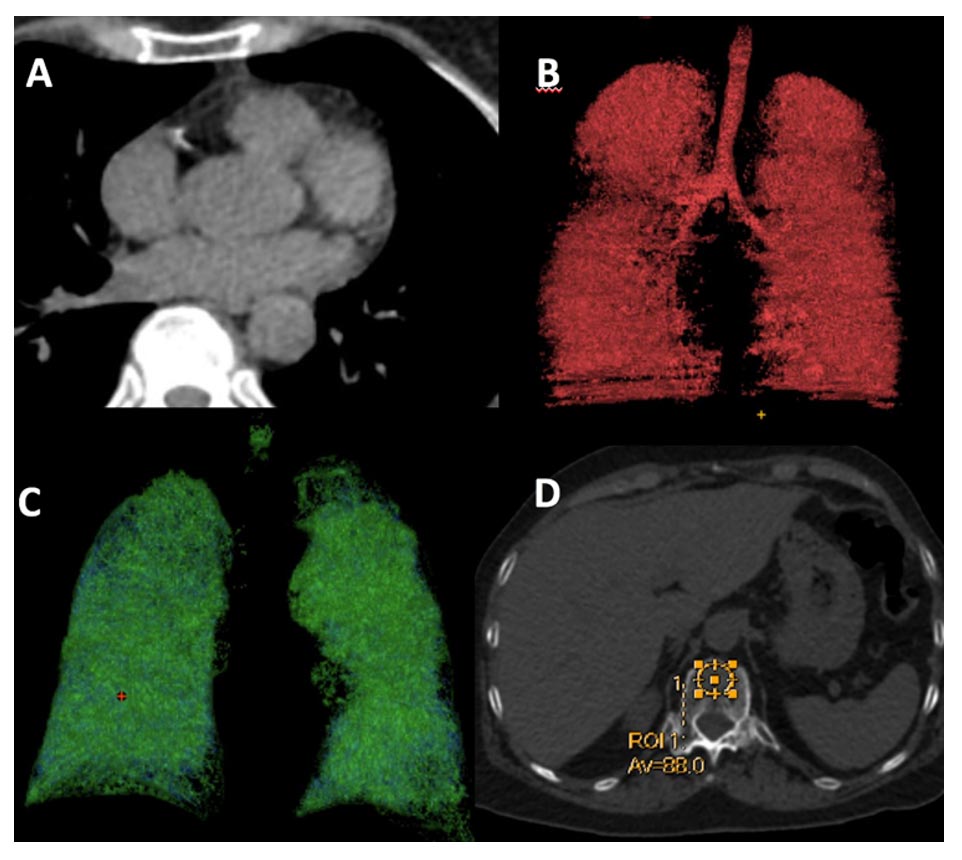

Chronic diseases related to smoking identified in previous lung cancer screening studies and commonly found in chest CT, include interstitial lung abnormalities (ILAs), and cardiovascular disease.11,12,13 ILAs are non-dependent abnormalities identified incidentally in patients without clinical suspicion interstitial lung disease (ILD), when ILD may be compatible with these abnormalities.14,15 Furthermore, there are subcategories of ILAs, non-subpleural; subpleural non-fibrotic, and subpleural fibrotic.13,14,15 Other smoking-related diseases identified in lung cancer screening studies and associated with lung cancer, such as hepatic steatosis and sarcopenia were also considered in this study.16,17 Sarcopenia is characterized by the loss of muscle mass and function and affects mainly elderly adults, like those participating in our study.18,19,20

The identification of these conditions in lung cancer screening participants is important, as it facilitates their treatment and improves the patients’ prognoses.11,21Chronic diseases are increasing in global prevalence and seriously threaten the ability of developing nations to improve the health of their populations. Although often associated with developed nations, the presence of chronic disease has become the dominant health burden in many developing countries. The rise of lifestyle-related chronic disease in poor countries is the result of a complex constellation of social, economic, and behavioral factors.22,23

In a recent study developed in Brazil, we demonstrated that smoking-related comorbidities (coronary arteriosclerotic disease, emphysema, ILAs, sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and hepatic steatosis) are prevalent in patients undergoing low-dose CT examination for lung cancer screening in developing countries (Fig. 1). These findings underscore the importance of integrated CT assessment as part of lung cancer screening, as the identification of such comorbidities provides the opportunity to address them, increasing the chances of improved prognoses and favorable outcomes for the participants.

Finally, we recognize that numerous obstacles will be encountered during the realization of lung cancer screening projects in Brazil and around the world. However, it is up to the agents of this cultural transformation to differentiate the real problems from those created by an unfair and unequal health system.

References

- 1. Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, Bahia L, Macinko J. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet 2011; 1(377):1778 -1797.

- 2. Cruz, J.A.W., da Cunha, M.A.V.C., de Moraes, T.P. et al. Brazilian private health system: history, scenarios, and trends. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 49 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07376-2

- 3. Ministério da Saúde- Brasil. Departamento de Análise em Saúde e Vigilância das Doenças Não Transmissíveis. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade (SIM). 2022. Available in: http://svs.aids.gov.br/dantps/centrais-de-conteudos/paineis-de-monitoramento/mortalidade/

- 4. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Análise em Saúde e Vigilância das Doenças Não Transmissíveis. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. VIGITEL BRASIL 2021.

- 5. Santos RS, Franceschini J, Kay FU, Chate RC, Costa Júnior Ada S, de Oliveira FN, Trajano AL, Pereira JR, Succi JE, Saad Junior R. Low-dose CT screening for lung cancer in Brazil: a study protocol. J Bras Pneumol. 2014 MarApr;40(2):196-9.

- 6. Santos RS, Franceschini JP, Chate RC, Ghefter MC, Kay F, Trajano AL, et al. Do Current Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines Apply for Populations with High Prevalence of Granulomatous Disease? Results From the First Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT1). Ann Thorac Surg. 2016 Feb;101(2):481-6.

- 7. Hochhegger B, Camargo S, Teles GBS, Chate RC, Szarf G, Guimarães MD, et al. Challenges of Implementing Lung Cancer Screening in a Developing Country: Results of the Second Brazilian Early Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT2). JCO Global Oncol. 2022;8:e2100257.

- 8. Zahnd WE, Eberth JM. Lung cancer screening utilization: a behavioral risk factor surveillance system analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(2):250-255. Medline:31248742 doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.015

- 9. Lung CT Screening Reporting & Data System (Lung-RADS). American College of Radiology. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Reporting-and-Data-Systems/Lung-Rads

- 10. Pinsky PF, Gierada DS, Black W, et al. Performance of Lung-RADS in the National Lung Screening Trial: a retrospective assessment. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(7):485-491. Medline:25664444 doi:10.7326/M14-2086

- 11. Regan EA, Katherine E. Lowe Ms, Barry J. Make MD, Gregory L. Kinney P, David A. Lynch MD, Matthew J. Budoff MD, Song Shou Mao P, Debra Dyer MD, Jeffrey L. Curtis MD, Russell P. Bowler MD, MeiLan K. Han MD, Terri H. Beaty P, Terri H. Beaty P, Terri H. Beaty P, Terri H. Beaty P, Terri H. Beaty P, Terri H. Beaty P, Terri H. Beaty P, Terri H. Beaty P, Terri H. Beaty P. Identifying Smoking-Related Disease on Lung Cancer Screening CT Scans: Increasing the Value. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases: Journal of the COPD Foundation 6: 233–245.

- 12. Brown S-AW, Padilla M, Mhango G, Powell C, Salvatore M, Henschke C, Yankelevitz D, Sigel K, de-Torres JP, Wisnivesky J. Interstitial Lung Abnormalities and Lung Cancer Risk in the National Lung Screening Trial. CHESTElsevier; 2019; 156: 1195–1203.

- 13. Hatabu H, Hunninghake GM, Richeldi L, Brown KK, Wells AU, Remy-Jardin M, Verschakelen J, Nicholson AG, Beasley MB, Christiani DC, San José Estépar R, Seo JB, Johkoh T, Sverzellati N, Ryerson CJ, Graham Barr R, Goo JM, Austin JHM, Powell CA, Lee KS, Inoue Y, Lynch DA. Interstitial lung abnormalities detected incidentally on CT: a Position Paper from the Fleischner Society. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 726–737.

- 14. Hata A, Schiebler ML, Lynch DA, Hatabu H. Interstitial Lung Abnormalities: State of the Art. RadiologyRadiological Society of North America; 2021; 301: 19–34.

- 15. Hino T, Lee KS, Yoo H, Han J, Franks TJ, Hatabu H. Interstitial lung abnormality (ILA) and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Eur J Radiol Open 2021; 8: 100336.

- 16. Chen X, Li K, Yip R, Perumalswami P, Branch AD, Lewis S, Del Bello D, Becker BJ, Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI. Hepatic steatosis in participants in a program of low-dose CT screening for lung cancer. Eur J Radiol2017; 94: 174–179.

- 17. Kawaguchi Y, Hanaoka J, Ohshio Y, Okamoto K, Kaku R, Hayashi K, Shiratori T, Akazawa A. Sarcopenia increases the risk of post-operative recurrence in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0257594.

- 18. Baumgartner RN, Stauber PM, McHugh D, Koehler KM, Garry PJ. Cross-sectional age differences in body composition in persons 60+ years of age. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1995; 50: M307-316.

- 19. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, Martin FC, Michel J-P, Rolland Y, Schneider SM, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Zamboni M. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age and Ageing 2010; 39: 412–423.

- 20. Derstine BA, Holcombe SA, Ross BE, Wang NC, Su GL, Wang SC. Skeletal muscle cutoff values for sarcopenia diagnosis using T10 to L5 measurements in a healthy US population. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 11369.

- 21. Chiles C, Duan F, Gladish GW, Ravenel JG, Baginski SG, Snyder BS, DeMello S, Desjardins SS, Munden RF, NLST Study Team. Association of Coronary Artery Calcification and Mortality in the National Lung Screening Trial: A Comparison of Three Scoring Methods. Radiology 2015; 276: 82–90.

- 22. Nugent R. Chronic diseases in developing countries: health and economic burdens. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008; 1136: 70–79.

- 23. Mattos J, Santos R, Hochhegger B, et al. CT on Lung Cancer Screening is useful for adjuvant comorbidity diagnosis in developing countries. ERJ Open Res. 2022 in press.