Inflammatory processes—acute and chronic—are hallmarks of both oncologic and mental disorders. Lung cancer cells, which are highly mutated with damage throughout the genome, hide from attack by low-antigen presentation, leading to immune-surveillance escape and suppression of the immune anti-cancer response. This process is generally thought to be initiated by carcinogenic exposure (i.e., tobacco), with pro-inflammatory pathways upregulated and anti-inflammatory ones downregulated.

Additionally, the biologic link between depression and smoking is known, as the neurotransmitter systems affected by cigarette smoke mirror the neurotransmitter pathways involved in the biologic mechanisms of depression.1 Among mental disorders, there is a long history of theory, evidence, and tests—both human and animal—that make the case for a bidirectional inflammation/depression duet,2,3 with elevations of proinflammatory cytokines and decreased adaptive immune responses taking center stage.

For example, meta-analytic data show blood levels of inflammatory biomarkers, including CRP, IL-3, IL-6, IL-12, IL-18, sIL-2R, and TNFα to be significantly elevated for those with depression.4 For those with lung cancer, inflammation5 and depression6 are, individually, predictive of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) survival, but the existence and extent of any covariation has been little studied, despite evidence for depression being a pro-inflammatory state.4

Here, our recent novel findings7 are briefly discussed and consideration is given to how the data might be considered in addressing depression-related morbidity and mortality in lung cancer patients.

In brief, we provided a positive test of the hypothesis that severity of patients’ depression would be significantly associated with prognostically poor inflammation. For this, three systemic inflammation ratio (SIR) biomarkers levels were calculated, and a validated assessment of self-reported depressive symptoms were obtained from stage-IV NSCLC patients at diagnosis. The three SIR biomarkers calculated were neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI). Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).

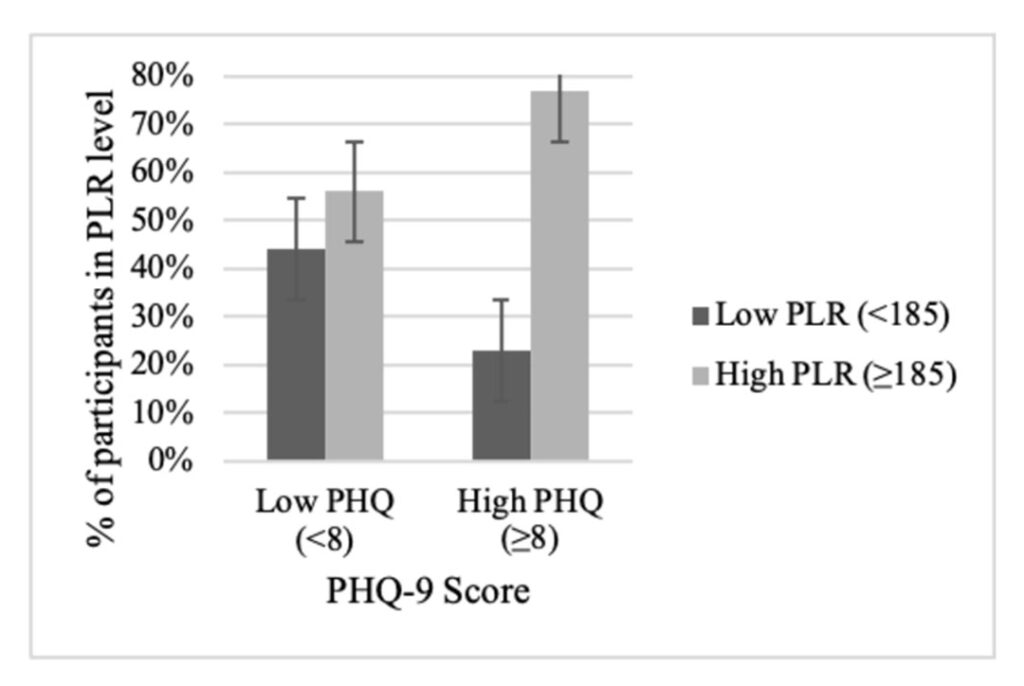

In preface to the primary analyses, Cox proportional models confirmed associations between each of the three inflammation biomarkers and shorter 2-year overall survival (OS) (ps < .005), a replication of SIR/OS effects reported by others.5,8 Data showed the severity of patients’ depressive symptoms to be reliably associated with elevations of the three inflammation biomarkers (p ≤ 0.02) predictive of OS. The 35% of the sample with moderate to severe depressive symptoms were 2- to 3-times more likely to have prognostically poor biomarker levels (i.e., NLR>5, PLR>185, ALI<24).

Figure 1 illustrates the effects at the patient level for PLR, showing the relationship between depression [PHQ-9<8 (none/mild) vs >8 (moderate to severe)] and systemic inflammation (PLR <185 vs. >185), yielding four patient groups determined by cutoffs. As shown, patients with moderate to severe depressive symptoms had disproportionately high inflammation indexed by PLR. Similar patterns were found for NLR and ALI.

The data suggest “cross talk” between cancer-specific and depression-specific inflammation processes, perhaps one mechanism for the scale of the depression problem in lung cancer.9,10 Of all cancer patients, lung cancer patients have the highest rates of moderate to severe symptoms, upwards of 30%,11 and the highest suicide rates.12

Many studies show depressive symptoms at diagnosis are predictive of survival. More persuasive are data showing that, when assessed monthly, the depressive symptom trajectory predicts survival, controlling for sociodemographics, smoking history, cancer type, and receipt of immunotherapy (+/-chemotherapy) and targeted treatments.6

Going forward, intensive study of depression combined with measures of cell biology, inflammation, and immunity are needed to extend these findings and discover the pathophysiology of depression linked to lung cancer progression. It is unknown why a substantial number of patients fail to respond to newer therapies for lung cancer or why some individuals with depression are treatment resistant.13

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) induce inflammation, but inflammation—such as high NLR—prior to ICI treatment is predictive of significantly poorer OS than for patients starting treatment with low NLR.14> It is unknown if patients’ depressive symptoms coupled with inflammation contribute to such effects. Other data show non-responders to antidepressant pharmacotherapy have been found with elevated inflammatory markers (TNF, CRP, IL-6).15

For the immediate term, thoracic oncologists and the medical team need to address the common problem of depression in their patients. New guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology6 are comprehensive, providing guidance for identifying and treating cancer patients with depression and/or anxiety.

Psychological/behavioral therapies are strongly recommended based on multiple metanalytic studies, with efficacy evidence for individual and group formats, tested with individuals, with or without cancer. By contrast, there was low evidence for pharmacologic treatments and the recommendation for its use is weak. Pharmacotherapy might be considered for patients who do not have access to first-line treatment, who prefer pharmacotherapy, or who do not improve following first-line psychological/behavioral management. Patients should be warned of potential harm or adverse effects.

Our future studies will determine if the high depression/high inflammation subgroup will be uniquely vulnerable to the continuation of depressive symptoms as they enter treatment, and if the depression/inflammation duet is predictive of OS, controlling for the baseline depression/inflammation and relevant sociodemographic, disease, and treatment variables. If confirmed, this would provide evidence for easily identifying and then treating patients with efficacious therapies for depression.16

Information on screening and treatment for cancer patients with depression and/or anxiety symptoms, can be found in Management of Anxiety and Depression in Adult Survivors of Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update.

References

- 1. Quattrocki, E., Baird, A. & Yurgelun-Todd, D. (2000). Biological aspects of the link between smoking and depression. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 8(3), 99 110. doi: 10.1080/hrp_8.3.99

- 2. Beurel, E., Toups, M. & Nemeroff, C.B. (2020). The bidirectional relationship of depression and inflammation: Double trouble. Neuron, 107(2), 234-256. doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.002.

- 3. Liu B-P, Zhang C, Zhang Y-P, Li, K-W., & Song, C. (2022) The combination of chronic stress and smoke exacerbated depression-like changes and lung cancer factor expression in A/J mice: Involve inflammation and BDNF dysfunction. PLoS ONE 17(11): e0277945. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277945

- 4. Osimo, E. F., Pillinger, T., Rodriguez, I. M., Khandaker, G. M., Pariante, C. M., & Howes, O. D. (2020). Inflammatory markers in depression: A meta-analysis of mean differences and variability in 5,166 patients and 5,083 controls. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 901-909. doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.02.010 R

- 5. Hua X, Chen J, Wu Y, Sha J, Han S, Zhu X. (2019). Prognostic role of the advanced lung cancer inflammation index in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. World Journal of Surgical Oncology, 17, 1–9.

- 6. Andersen, B.L., Lacchetti, C., Ashing, K., Berek, J.S., Berman, B.S., Bolte, S. … Rowland, J.H. (2023). Management of anxiety and depression in adult survivors of cancer: ASCO Guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology, Apr 19. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.00293

- 7. Andersen, B.L., Blevins, T.R., Park, K.P., Smith, R.M., Reisinger, S., Carbone, D.P., Presley, C.J., Shields, P.G., & Carson, W.E. (2023). Depression in association with neutrophil-to-lymphocyte, platelet-to-lymphocyte, and advanced lung cancer inflammation index biomarkers predicting lung cancer survival. PLoS ONE 18(2), e0282206. doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0282206

- 8. Zhou, Q., Su, S., You, W., Wang, T., Ren, T., & Zhu, L. (2021). Systemic inflammation response index as a prognostic marker in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 cohorts. Dose-Response, 19(4), 15593258211064744, 1-14.

- 9. Borovcanin, M.M., Vesic, K., Arsenijevic, D., Milojevic-Rakic, M., Mijailovic, N.R.; Jovanovic, I.P. (2023). Targeting underlying inflammation in carcinoma is essential for the resolution of depressiveness. Cells, 12, 710. doi.org/10.3390/cells12050710

- 10. Young, K. & Singh, G. (2018). Biological mechanisms of cancer-induced depression. Frontiers of Psychiatry, 9, 299. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00299

- 11. Andersen, B.L., Valentine, T.R., Lo, S.B., Carbone, D.P., Presley, C.J., Shields, P.G. (2020). Newly diagnosed patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A clinical description of those with moderate to severe depressive symptoms. Lung Cancer, 145, 195-204.

- 12. Heinrich, M., Hofmann, L., Baurecht, H., Kreuzer, P.M., Knüttel, H., Leitzmann, M.F. & Seliger, C. (2022). Suicide risk and mortality among patients with cancer. Nature Medicine, 28, 852-859.

- 13. Gaynes, B. N., Lux, L., Gartlehner, G., Asher, G., Forman‐Hoffman, V., Green, J., E., Weber, R.P., Randolph, C., Bann, C., Coker-Schwimmer, E., Viswanathan, M., & Lohr, K. N. (2020). Defining treatment‐resistant depression. Depression and Anxiety, 37(2), 134-145. doi.org/10.1002/da.22968

- 14. Cortellini, A., Ricciuti, B., Borghaei, H., Naqash, A. R., D’Alessio, A., Fulgenzi, C. A., & Pinato, D.J. (2022). Differential prognostic effect of systemic inflammation in patients with non–small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy or chemotherapy: A post hoc analysis of the phase 3 OAK trial. Cancer, 128(16), 3067-3079.

- 15. Haroon, E., DaJuan, A.W., Woolwine, B.J., Goldsmith, D.R., Baer, W.M., Wommack, E.C., Felger, J.C. & Miller, A.H. (2018). Antidepressant treatment resistance is associated with increased inflammatory markers in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 95, 43–49. doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.026

- 16. Arrato, N.A. Lo, S., Presley, C.J., & Andersen, B.L. (in prep.) Stress and immunity in lung cancer: A Biobehavioral/cognitive treatment for depression and anxiety.

- 17. Andersen, B.L. McElroy, J.P., Carbone, D.P., Presley, C.J., Smith, R.M., Shields, P.G., & Brock, G.N. (2020). Psychological symptom trajectories and non-small cell lung cancer survival: A joint model analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 84, 215-223.

- 18. Management of Anxiety and Depression in Adult Survivors of Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update Q&A