The past 10 years have seen a dramatic increase in novel therapeutic options for patients with lung cancer, with many treatments now personalized to the specific tumor characteristics of each patient’s disease.1,2 The majority of these novel therapies are either immunotherapies or molecularly targeted agents. Identification of the best therapeutic option for every patient before initiation of treatment is paramount for achieving the best outcomes. When available, molecularly targeted therapies provide the best outcomes for patients who have advanced-stage NSCLC with driver mutations, but their use depends on timely identification of oncogenic drivers through biomarker testing. In a rapidly changing field with frequent approval of new therapies and evolving evidence, getting the right treatment to the right patient at the right time is no trivial task.

Evidence-based international guidelines, from the College of American Pathologists (CAP), the IASLC, and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), have recommended biomarker testing for all patients with advanced-stage non-squamous NSCLC since 2013, with a revision in 2018.3 However, anecdotal evidence suggested that concordance with guidelines on molecular testing is not universal. To better understand the landscape of and barriers to molecular testing across the world, the IASLC conducted a survey of lung cancer providers.4

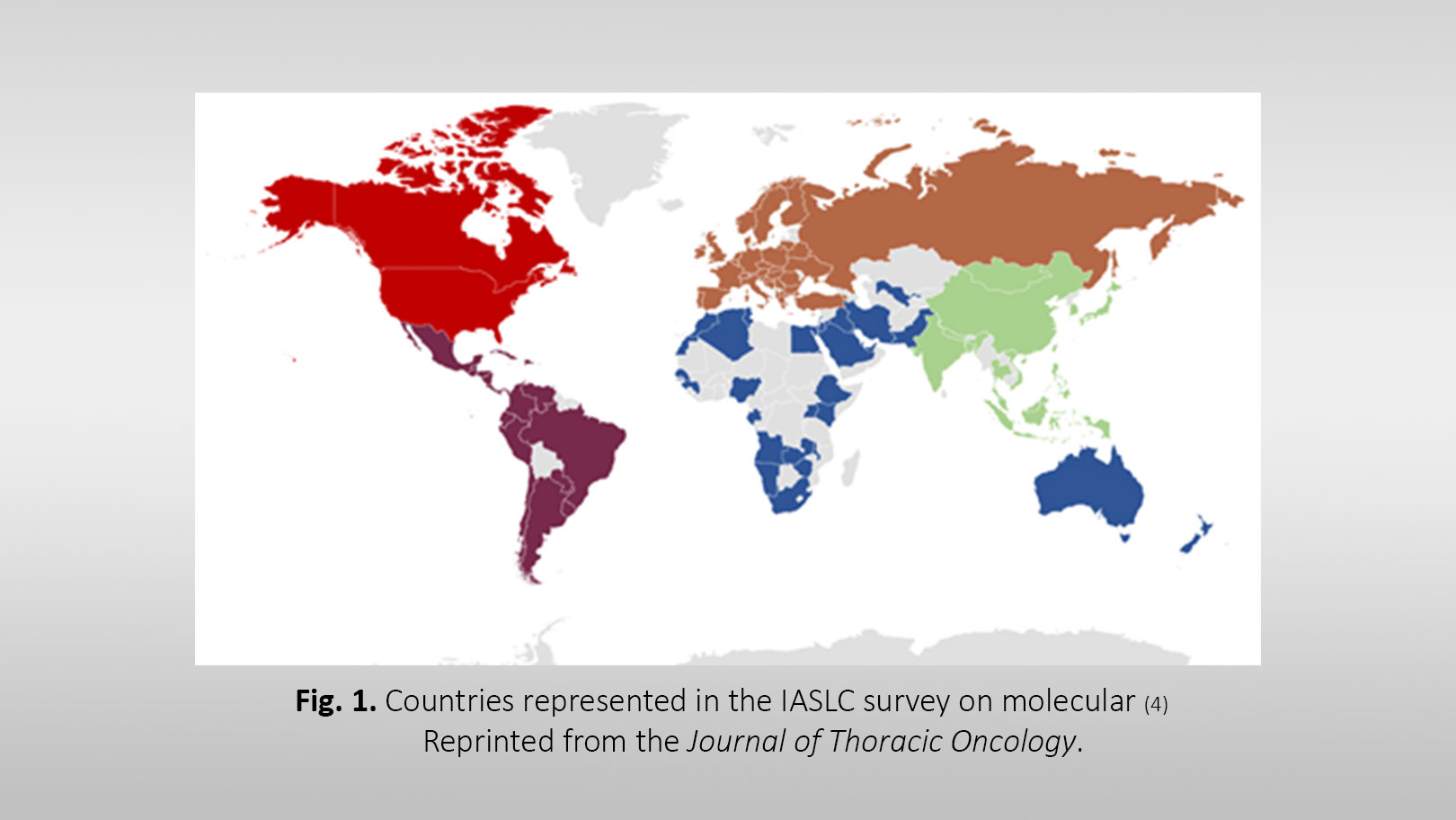

The IASLC survey on molecular testing in lung cancer included 33 to 54 questions in three tracks, on the basis of the responding provider’s role (requesting molecular tests, analyzing assays, acquiring tissue). The IASLC received 2,537 responses from providers in 102 countries, 56% of which were from developing countries (Fig. 1). Results from this survey suggested substantial deficits in awareness of and adherence to current guidelines. Many respondents (33%) were not aware of the 2018 CAP/IASLC/AMP guidelines. Respondents estimated that fewer than 50% of patients with lung cancer receive molecular testing, and many who are tested may receive testing only for EGFR and ALK molecular markers. Many respondents expressed dissatisfaction with the current state of molecular testing for lung cancer in their countries of practice but frequently reported no policy or strategy to improve molecular testing.

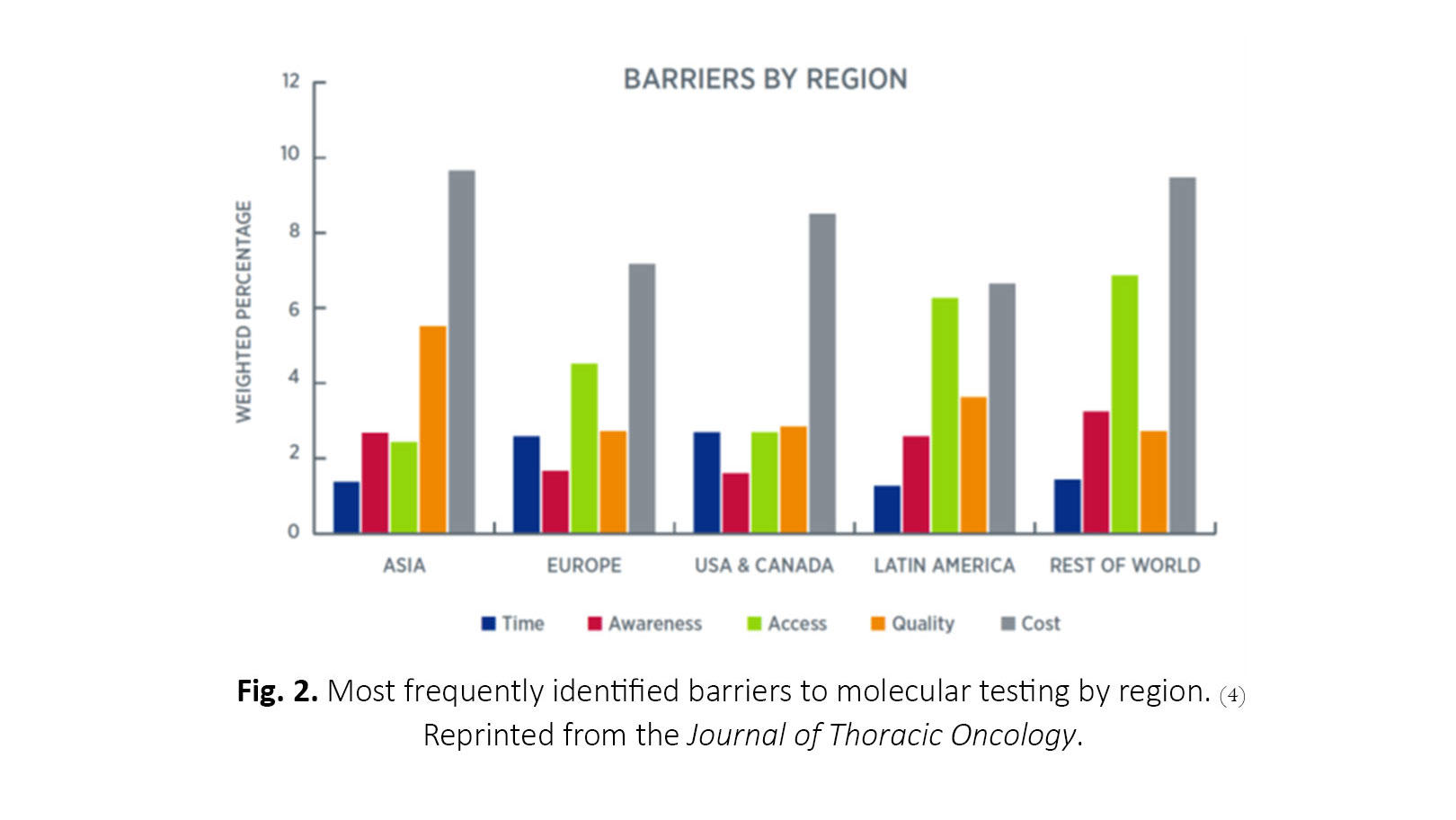

The barriers to testing most frequently identified across all regions include cost, quality and standards, access, awareness, and turnaround time (Fig. 2). Cost was the most frequent barrier in all regions, and the primary payer varied across and within regions but most commonly included out-of-pocket payment by the patient, government entities, pharmaceutical companies, or private health insurance. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is particularly cost-prohibitive in many countries, although its utility continues to increase as more potentially targetable biomarkers are discovered. There is great opportunity to reduce the barrier of cost by improving communication and understanding among patients, providers, and payers. Quality and standards concerns were highest in Asia and Latin America.

Working across medical disciplines to develop more specific testing protocols and systematic processing of samples could help improve both the timing of testing and optimization of tissue.

Institutions may look to implement process-level improvements for increasing adherence to molecular testing guidelines. Specific protocols to initiate include guideline-recommended reflex testing of all appropriate patients, management of small-tissue specimens, and follow-up liquid biopsy testing for inconclusive results from the primary tissue biopsy. Pathologists should be encouraged to adhere to updated CAP guidelines.3,5

Dissemination and Adoption of Guidelines

The IASLC survey indicated that suboptimal awareness and adoption of evidence-based guidelines are barriers to molecular testing in lung cancer. We still have work to do to improve uptake of guidelines across the spectrum of lung cancer providers. Continuous education for community care physicians, including medical oncologists, pulmonologists, interventional radiologists, and pathologists, should be intensified. This could emphasize a more positive message of far superior outcomes for patients with lung cancer treated with appropriate therapy. The IASLC plans to initiate an awareness campaign, incorporating short videos from young investigators, and launch a social media campaign that will target the barriers identified for all specialties involved in lung cancer care. Online development of modular learning methods for biomarker testing and precision medicine could prove to be useful. The electronic-learning methods should be optimized to fit every device and incentivize the learner.

Patient advocacy groups play a critical role in increasing awareness of biomarker testing, as exemplified by a recent collaborative effort to standardize terminology, which has been endorsed broadly.6 Educational efforts such as targeted webinars, podcasts, social media postings, email blasts, newsletters, and sessions at all national and international meetings on all aspects of biomarker testing will, we hope, help break down the barriers that currently limit testing.

Recommended Targets for NGS

Although sequential individual biomarker testing has been the standard in many settings, a broader NGS approach is becoming more cost effective. The number of targetable mutations continues to increase rapidly, with four new targeted therapies approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020 thus far. In the United States, FDA-approved targeted therapies are now available for EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF V600E, NTRK, MET, and RET, making the 2018 guidelines already outdated.1 Preliminary evidence presented from the ADAURA trial in 2020 also suggests that there could be demonstrable benefit from targeted therapies in patients with early-stage lung cancer.7 Therefore, there is a need for standardized recommendations for molecular testing that are quickly adaptable, given the dynamic changes that are occurring at a rapid pace. At a minimum, guidelines should now recommend testing of all markers for which there are FDA-approved drugs. A more fluid approach could include a general testing guideline that points to a regularly updated list of recommended targets to be included in NGS panels, with primary recommendations for FDA-approved targets and secondary recommendations for targets with agents in development. These can vary regionally depending on availability of agents in different parts of the world, but awareness of the molecular targets in a given tumor can be of value to patients even if targeted agents are not yet available. Furthermore, the future is bright for precision medicine, as advancing technologies using artificial intelligence tools, such as the one from the TRACERx (TRAcking Cancer Evolution through therapy [Rx]) lung study, will prove to be complementary to NGS.8

Interventions should be broadly applicable to oncology practices worldwide. Advancements in therapeutic options based on biomarker testing for patients bring great hope for the lung cancer community; we must work together to ensure that all patients have an opportunity to benefit from state-of-the-art care.

References:

- Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, et al. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):41-50.

- Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, et al. Brigatinib versus crizotinib in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2027-2039.

- Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Aisner DL, et al. Updated molecular testing guideline for the selection of lung cancer patients for treatment with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Guideline from the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(3):323-358.

- Smeltzer MP, Wynes MW, Lantuejoul S, et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Global Survey on Molecular Testing in Lung Cancer. J Thor Oncol. 2020;15(9):1434-1448.

- Collection and handling of thoracic small biopsy and cytology specimens for ancillary studies. College of American Pathologists. May 12, 2020. Accessed August 19, 2020. https://www.cap.org/protocols-and-guidelines/upcoming-cap-guidelines/co…

- A white paper on the need for consistent terms for testing in precision medicine. July 2020. Accessed August 25, 2020. https://www.commoncancertestingterms.org/files/Consistent-Testing-Termi…

- Herbst RS, Tsuboi M, John T, et al. Osimertinib as adjuvant therapy in patients (pts) with stage IB–IIIA EGFR mutation positive (EGFRm) NSCLC after complete tumor resection: ADAURA. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(suppl). Abstract presented at: ASCO Virtual Scientific Program; May 29-31, 2020. Abstract LBA5.

- Jamal-Hanjani M, Hackshaw A, Ngai Y, et al. Tracking genomic cancer evolution for precision medicine: the lung TRACERx study. PLOS Biology. 2014;12(7):e1001906.