Invasive or not invasive—that is the question. What is the answer and how consistent are pathologists at recognizing it?

The Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary, defines invasion as “local spread of a malignant neoplasm by infiltration or destruction of adjacent tissue; for epithelial neoplasms, invasion signifies infiltration beneath the epithelial basement membrane.” In non-mucinous adenocarcinomas of the lung (LUAD), this seemingly straightforward concept is far more complicated than meets the eye given the dynamic anatomy of the lung and the inherent histologic heterogeneity of LUAD.

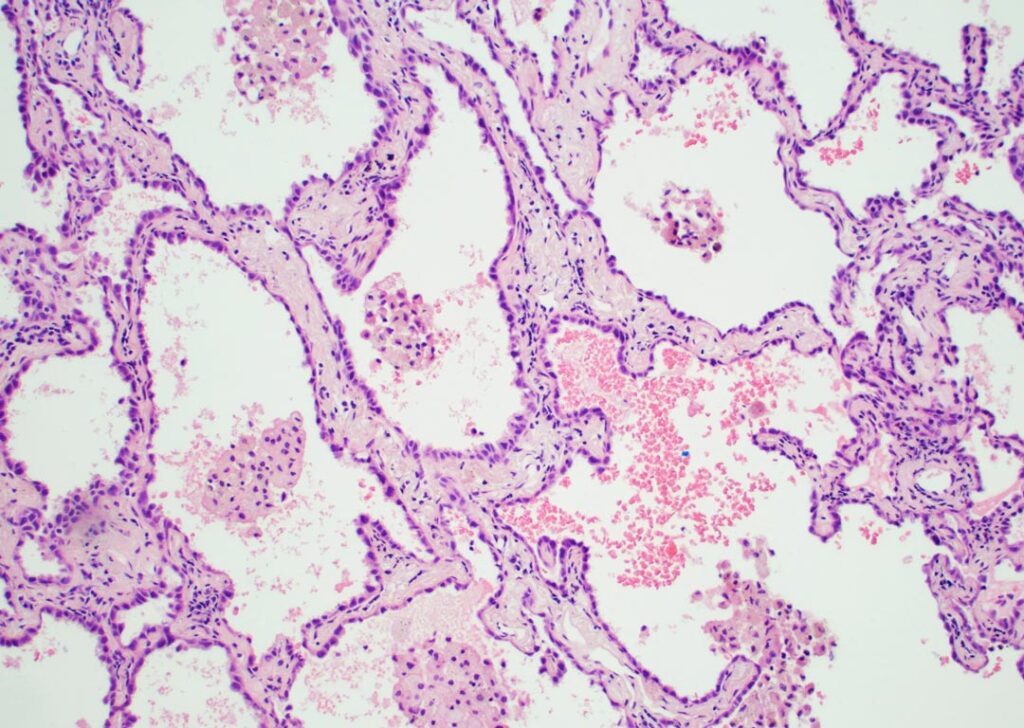

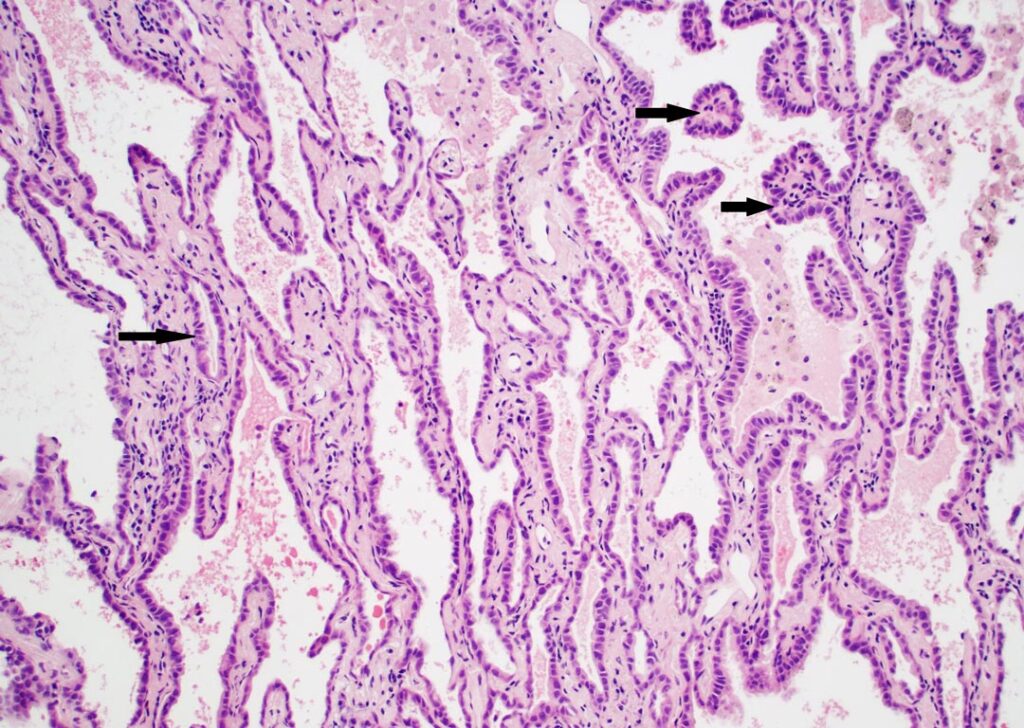

According to the current World Health Organization (WHO) classification of thoracic neoplasms, non-invasive growth in LUAD is characterized by a lepidic pattern, defined as tumor cells growing along pre-existing alveolar walls without destruction of lung architecture. Patterns of invasion in LUAD include acinar, papillary, micropapillary and solid.1 Variants such as cribriform, complex and fused gland patterns, while not included in the WHO classification currently, are also recognized as patterns of invasion with a poor prognosis.2

Invasive carcinoma, as encountered in most solid organs, typically destroys normal tissue and frequently elicits a desmoplastic response. This is not always the case in the lung. While some invasive patterns do adhere to this principle, others, particularly papillary and micropapillary growth patterns, grow into alveolar airspaces rather than destroying lung architecture. Furthermore, a unique issue with lung tissue is the influence of alveolar collapse, which may be iatrogenic due to issues with specimen handling such as compression and subsequent poor inflation. Such collapse may create difficulties in discriminating between lepidic, papillary, and acinar patterns, in particular, and is discussed further below. In addition to iatrogenic issues surrounding collapse, other factors such as poor fixation and tangential sectioning may also impact interpretation.

Non-mucinous LUAD are currently classified as adenocarcinoma in situ (pure lepidic growth); minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (lepidic growth with ≤ 5mm of invasion); or, in tumors with greater than 5mm of invasion, invasive adenocarcinoma with further classification by the predominant subtype and a recommendation that additional growth patterns be documented with all patterns quantified in 5% increments. The predominant histologic subtype has been shown to correlate with prognosis, with lepidic predominant tumors having the best prognosis, and micropapillary and solid tumors having the worst prognosis.

While providing better prognostic information than prior classifications, the “predominant subtype” classification did not accurately convey the negative impact of small components of poor prognostic components (micropapillary, solid, or cribriform/complex gland patterns).

A recently proposed grading system from the IASLC Pathology Committee accounted for this problem by assigning grade 1 to lepidic predominant LUAD, grade 2 to acinar or papillary predominant LUAD, and grade 3 to any LUAD with >20% of a poor prognostic component.2 As such, recognition of invasive versus non-invasive components, as well as patterns, has implications for prognostic stratification and grading.

More critically, recognition of invasive versus non-invasive growth also has implications for staging. In the eighth edition of the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification, the pT category of any non-mucinous LUAD with a component of lepidic growth is based on the measurement of the invasive component only, exclusive of the lepidic component.4,5 As such, accurate identification of invasion is critical for both grading and staging.

Furthermore, in some centers, pathologists are asked to determine the presence or absence of invasion on frozen section to determine whether a lobectomy or sublobar resection will be performed. However, it has long been recognized that intra-observer agreement for histologic patterns has only been moderate to fair.6,7 Perhaps not unexpectedly, intra-observer agreement regarding measurement of the size of the invasive component suffers from similar problems.6

Reproducibility, Evaluation of Tumor Size in Part-solid Tumors

In a recent issue of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology, Thunnissen et al present the work of the invasion working group of the IASLC Pathology Committee.8 This work was undertaken to address a research question posed in the IASLC lung cancer staging document regarding reproducibility and best methods for evaluation of tumor size in part-solid tumors, which typically correspond to tumors with a lepidic component. The participants were asked to evaluate tumors with what was felt to be a mixture of invasive and non-invasive (lepidic) growth. While there was excellent concordance in measuring overall tumor size, there was poor agreement regarding measurement of invasive tumor size.

Following an effort to address the binary question of invasive versus not invasive, areas of disagreement were evaluated, and features were identified that improved intra-observer agreement. Given that small LUAD with peripheral lepidic growth generally have a good prognosis, a question that needed to be addressed was “how do you know who is right?” To this point, nine tumors that had either lymph node metastasis or recurrence were included.

Key features that were consistently associated with invasion in this context included, as expected, desmoplastic stroma or growth of malignant cells within the stroma of alveolar walls but, as discussed above, these changes are not characteristic of all invasive growth patterns in LUAD. Invasive tumors frequently had greater cytologic atypia than non-invasive tumors, often with a transition between the two. Intraluminal alveolar macrophages were frequently absent in invasive areas, but their presence is not a definitive sign of non-invasive tumor given they may be present in association with certain invasive patterns of spread such as micropapillary growth. This latter change is not unexpected since micropapillary growth may be present within a pre-existing alveolar space, where we may also find alveolar macrophages

There were two key histologic features that led to lack of agreement on the presence of invasion:

- Areas of alveolar collapse

- A newly described feature of “extensive epithelial proliferation”

In tumors with lepidic growth, tumor cells grow along pre-existing alveolar structures, and, as such, are associated with retained lung architecture. Alteration of this architecture would theoretically signify invasion. However, this assessment is frequently confounded by the presence of alveolar collapse and may be further compounded by fibrosis within the alveolar walls. It was noted that where alveolar collapse in areas of lepidic growth of tumor resulted in a potential impression of invasive glandular structures, these structures were typically arranged in a parallel streaming configuration as opposed to irregular infiltration more typical of true invasion. Elastin stains demonstrating retention of the preserved elastic framework of the lung and cytokeratin 7 staining to highlight the parallel growth pattern were felt to be useful in some, but not all, cases.

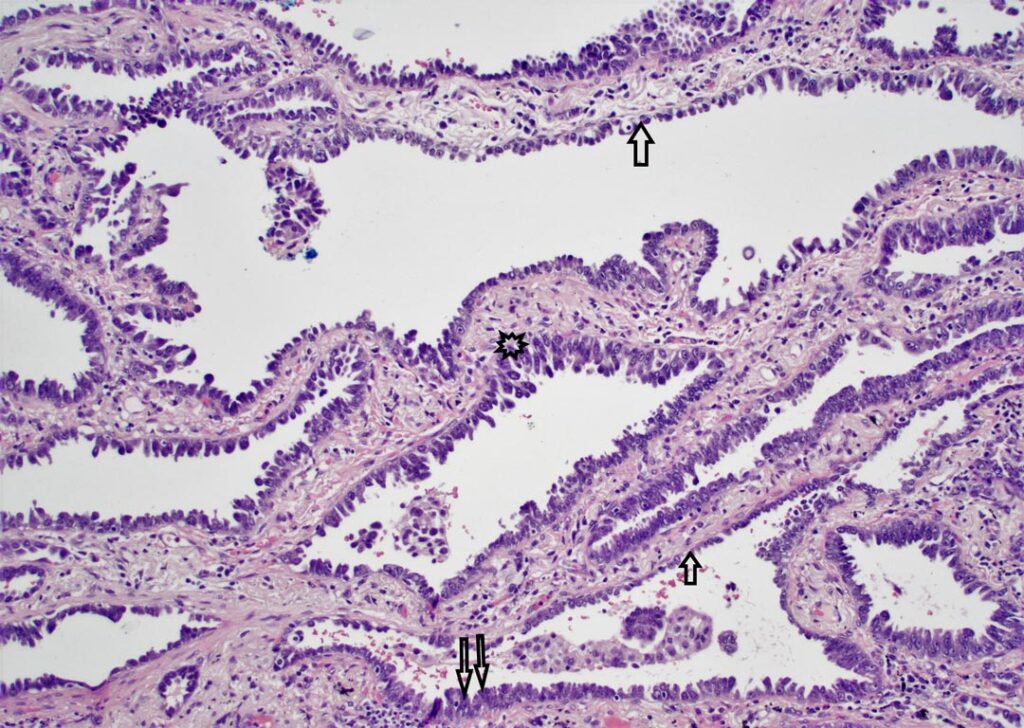

Extensive epithelial proliferation (EEP) was identified as being indicative of invasion during the analysis and was defined as an epithelial proliferation lining alveolar spaces that would otherwise be classified as lepidic, but with a cellular proliferation of two or more layers in thickness, as opposed to a monolayer characteristic of lepidic disease. Such areas also typically had high grade cytologic features, and there was frequently a transition between EEP and areas of monolayered lepidic growth. This observation improved reproducibility in answering the binary question of invasion versus not invasion when EEP was incorporated into the invasive size.

However, this requires further evaluation and refinement and raises other questions.

Yotsukura et al,9 demonstrated that a lepidic pattern with two cell layers or less was associated with a 100% survival, so further study is needed to determine if non-invasive growth should be strictly limited to a monolayer, two cell layers, or some other cut off.

Additionally, it is unclear whether EEP represents true invasion or is a surrogate for invasion elsewhere in the tumor. Further, discriminating EEP from patterns associated with aggressive behavior—which may themselves represent a continuum, such as the “low papillary” growth described by Fukutomi, et al10—as well as filigree and conventional patterns of micropapillary adenocarcinoma11, requires further study. This is no small matter given the prognostic implications of micropapillary growth and influence on tumor grade. Further complicating matters, interpretation of foci as micropapillary carcinoma may be influenced by tangential sectioning and other issues.

Given the implications for staging in particular, the identification and rigorous evaluation of features resulting in discordance in measuring invasive tumor size by the working group, while requiring further study and validation, will hopefully improve reproducibility and lead to more accurate tumor staging moving forward. While complete concordance is unlikely, the question of “invasion or not invasion” will hopefully have a more accurate and precise answer based on these efforts.

References

- 1. Nicholson AG, Tsao MS, Beasley MB, et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Advances Since 2015. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17:362-87.

- 2. Moreira AL, Ocampo PSS, Xia Y, et al. A Grading System for Invasive Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma: A Proposal From the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Pathology Committee. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:1599-610.

- 3. WHO Classification of Tumours. Thoracic Tumours. 5th ed: IARC; 2021.

- 4. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:39-51.

- 5. Travis WD, Asamura H, Bankier AA, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Coding T Categories for Subsolid Nodules and Assessment of Tumor Size in Part-Solid Tumors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1204-23.

- 6. Shih AR, Uruga H, Bozkurtlar E, et al. Problems in the reproducibility of classification of small lung adenocarcinoma: an international interobserver study. Histopathology 2019;75:649-59.

- 7. Thunnissen E, Beasley MB, Borczuk AC, et al. Reproducibility of histopathological subtypes and invasion in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. An international interobserver study. Mod Pathol 2012;25:1574-83.

- 8. Thunnissen E, Beasley MB, Borczuk A, et al. Defining Morphologic Features of Invasion in Pulmonary Nonmucinous Adenocarcinoma With Lepidic Growth: A Proposal by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Pathology Committee. J Thorac Oncol. 2023;18(4):447-462. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2022.11.026

- 9. Yotsukura M, Asamura H, Suzuki S, et al. Prognostic impact of cancer-associated active fibroblasts and invasive architectural patterns on early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2020;145:158-66.

- 10. Fukutomi T, Hayashi Y, Emoto K, Kamiya K, Kohno M, Sakamoto M. Low papillary structure in lepidic growth component of lung adenocarcinoma: a unique histologic hallmark of aggressive behavior. Hum Pathol 2013;44:1849-58.

- 11. Emoto K, Eguchi T, Tan KS, et al. Expansion of the Concept of Micropapillary Adenocarcinoma to Include a Newly Recognized Filigree Pattern as Well as the Classical Pattern Based on 1468 Stage I Lung Adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:1948-61.