In the United States, racial disparities in lung cancer incidence are known to exist. This is most likely caused by higher smoking prevalence among non-Hispanic Black adults compared to non-Hispanic White adults.1

In addition, a higher tobacco-associated lung cancer risk for Black adults has been observed.2

Recently, Jemal et al. described their findings of changes in the difference in lung cancer incidence among Black and White young adults.3

The authors expanded their earlier database findings with additional age cohorts and a more extended period. They obtained data on lung cancer cases diagnosed in people ages 30 to 54 between 1997 and 2016 from the Cancer in North America Database,4

which covers nearly the entire U.S. population. Race and ethnicity were categorized according to Hispanic origin as non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks. Age was categorized by 5-year age intervals (from 30-34 to 50-54 years), and year of diagnosis by 5-year calendar period (from 1997-2001 to 2012-2016).

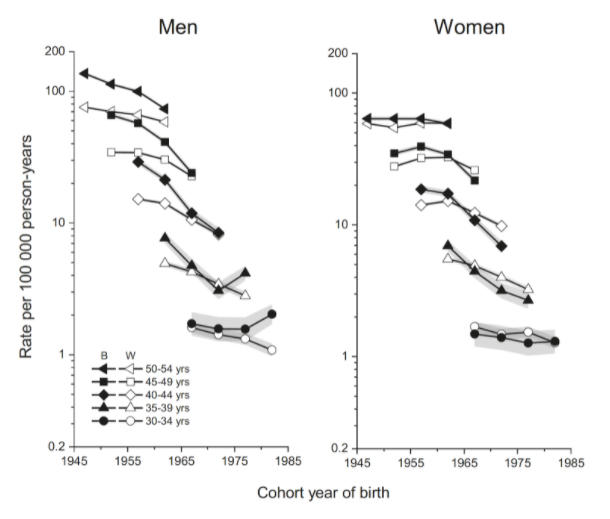

The main finding was that the historically higher lung cancer incidence rates in Black young adults than White young adults have disappeared in the population of men born between 1967 and 1972 and have been reversed in the population of women born since about 1965 (Fig.). This finding is consistent with the smoking prevalence in Black and White people by sex, which shows a steeper decline in smoking prevalence in Black people than in White people. The steeper decline in cigarette smoking among Black teenagers compared to White teenagers is thought to be multifactorial. Stronger parental and community nonsmoking norms, a more prominent perception of smoking’s health hazards, and increased participation in sports are reasons for this. Another potential reason is the price of cigarettes, which could have a more considerable influence due to differences in socioeconomic status.

B indicates non-Hispanic Black; W, non-Hispanic White. Shaded bands indicate incidence rates: 95% confidence intervals.

One notable exception is an increase in the prevalence of cigarette use among Black high school students, which doubled from 14.1% to 28.2% between 1991 and 1997. This steep rise in the initiation of smoking among Black adolescents in the 1990s coincided with the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company’s tobacco advertisements targeting Black individuals. The increasing lung cancer incidence rates in Black men born between about 1977 and 1982 is likely a direct result of that campaign. This finding emphasizes the need for tobacco regulation.

Another finding in this same cohort was that lung cancer incidence was higher in Black adults than in White adults, whereas smoking prevalence was similar between Black and White adults. Even so, the number of cigarettes smoked per day was lower in Black adults, which adds to the hypothesis that there is an increased risk of NSCLC associated with cigarette smoking in Black adults. So, where do we go from here? As is commonly known, tobacco regulation is the key to lower lung cancer incidence, and the decline of lung cancer incidence seen in this study is a result of anti-tobacco public health policies. However, the numbers in this study also detect an increase in lung cancer due to a single tobacco-marketing campaign and reveal what can happen if we let down our guard. The steeper decline in Black adults than in White adults is thought to be multifactorial, of which differences in socioeconomic status are a possible contributing factor. Worldwide, the price of cigarettes is indeed inversely correlated with smoking prevalence. For example, with a 20 pack of regular cigarettes now costing more than US $25 in Australia, smoking prevalence in people age 14 and older dropped from 24% in 1991 to 11% in 2019.5

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Smoking. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/behaviours-risk-factors/smoking/ov… As more countries are increasing their cigarette prices, we can hope that smoking incidence will drop among all ethnicities.

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Smoking. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/behaviours-risk-factors/smoking/ov…

- 2. Stram DO, Park SL, Haiman CA, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in lung cancer incidence in the multiethnic cohort study: an update. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019; 111(8):811-819.

- 3. Jemal A, Miller KD, Sauer AG, et al. Changes in Black-White difference in lung cancer incidence among young adults. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(4):pkaa055.

- 4. NAACCR CiNA Public Dataset. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. 1995-2020. Accessed December 30, 2020.

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Smoking. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/behaviours-risk-factors/smoking/ov…