Skyler B. Johnson, MD

A recent annual survey by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) suggested that approximately 40% of individuals believe that unproven therapies, used alone, can cure cancer.1

This is a startling finding and the likely result of cancer misinformation, which we define as cancer-related claims that are false based on contemporary scientific consensus2. Cancer treatment misinformation likely has many sources that are, unfortunately, amplified by the internet, where false information has been shown to spread farther, faster, and more broadly than truthful information.3 Addressing misinformation is a critical public health priority, and as such, several high-profile editorials have been published that call on researchers, providers, and organizations to address the impacts of false therapeutic claims on the delivery of evidence-based treatment.

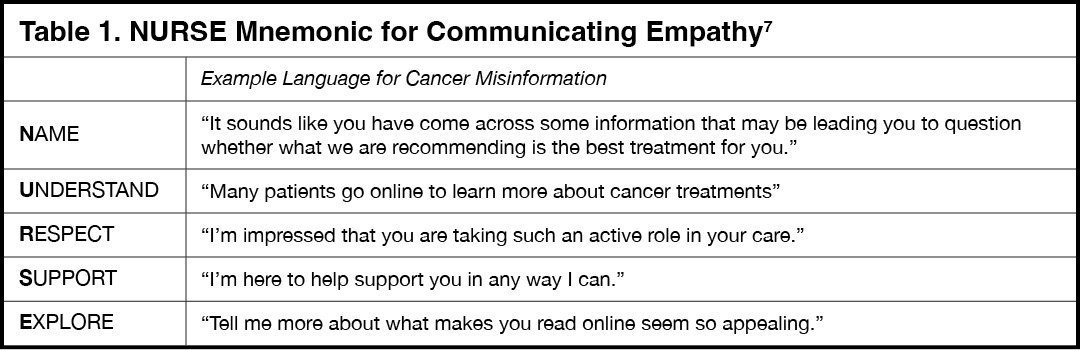

In response, we conducted a study titled “Cancer Misinformation and Harmful Information on Facebook and Other Social Media: A Brief Report,” published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.4 In the study, reviews of the most popular articles about cancer found on Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, and Pinterest were conducted by National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) experts, whose findings demonstrated that nearly one in three articles about cancer contained misinformation and, of those, 77% contained harmful information. More concerning was that articles that contained misinformation and harmful information were likely to receive a higher level of engagement online, via shares, comments, and likes, than accurate and safe information (Fig. 1).4

Fig. 1. Box plots showing the association of total online engagements with cancer articles defined as A) factual and misinformation, and B) safe and harmful. P values were calculated using a 2-sided 2-sample Wilcoxon rank sum (Mann-Whitney test). Medians are shown within boxes that represent the interquartile ranges and the error bars that represent the ranges with outside values excluded. Figure adapted from previous work by Johnson et al. 4

How Misinformation Affects Patients with Cancer

Cancer misinformation can affect treatment decision making with grave consequences. We previously reported on predictors of the use of unproven therapies, either alone5 or with one or more conventional cancer therapies6, as well as subsequent health outcomes, demonstrating that unproven therapies are associated with higher mortality rates for those with potentially curable cancers than recommended conventional therapies such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

When controlling for age, cancer type, gender, race, income, education, residence setting, residence location, insurance type, facility type, clinical stage, and comorbidity score, we found that patients with lung cancer were significantly more likely to select alternative medicine (odds ratio 3.16, 95% CI [1.85-5.40]) than patients who had prostate cancer.

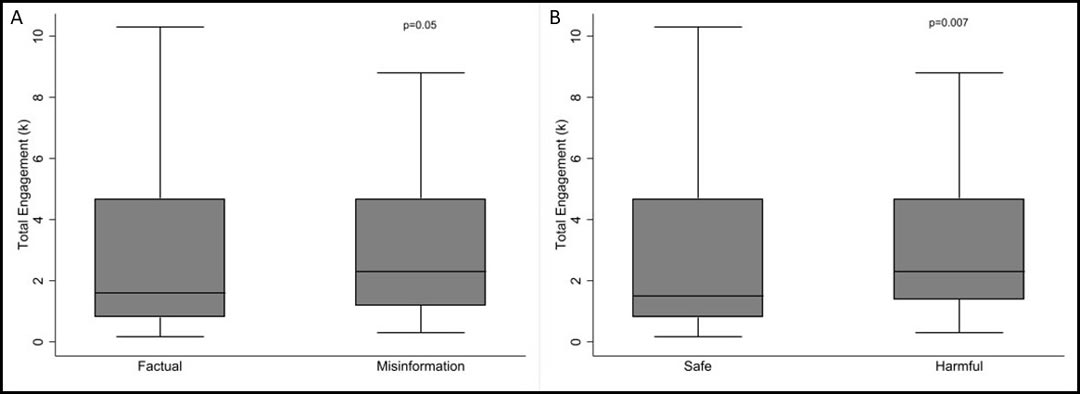

Alarmingly, the use of unproven cancer therapies by those with lung cancer was associated with statistically significantly worse 5-year OS compared with the use of recommended treatments (20% [95% CI (10%-32%)] vs. 41% [95% CI (31%-51%), p<0.001; Fig. 2]), and was an independent predictor of greater risk of death when controlling for clinical and sociodemographic factors (HR 2.17, 95% CI [1.42-3.32]).5

Fig. 2. Overall survival of lung cancer patients receiving unproven cancer treatments or ‘alternative medicine (solid lines)’ vs conventional cancer treatment (dashed lines). P values were calculated by a two-sided log-rank test. Figure adapted from previous work by Johnson et al.5

Mitigating the Impacts of Cancer Misinformation

Cancer misinformation not only affects survival by hindering the delivery of evidence-based therapies, but it threatens public health by eroding trust and negatively impacting patient-physician relationships. A major challenge in clinical oncology is the dissemination of accurate, effective, and evidence-based information to educate patients and caregivers.

Here, we outline several mitigation strategies that should be explored at community and patient levels to address cancer misinformation:

- Improve online health literacy.

- Encourage healthcare providers to play active roles on social media as first responders to misinformation.

- Engage cancer treatment stakeholders in producing high-quality, safe, and accurate information. Stakeholders include patients and their caregivers, healthcare providers, patient advocacy and support groups (including Facebook cancer group administrators), research funding agencies, nonprofit organizations, health information technology organizations, and government agencies.

- Inoculate patients against misinformation by warning them they will likely encounter it online and educate them on sources of high-quality and accurate information.

- Identify warning signs of online misinformation: Conspiracy theories, claims too good to be true, requests for money, anecdotes/testimonials, lack of a credible publisher/author, and/or non-verifiable or unsupported claims based on current scientific evidence.

- Improve patient-physician alliance.

- Check for understanding by asking a question like: “On a scale from 1-10, how confident are you in our recommendation to proceed with chemotherapy and radiation? Why isn’t it a 1? Why isn’t it a 10?”

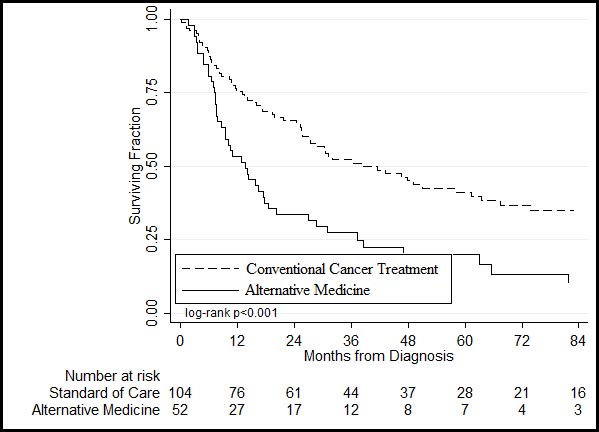

- Show empathy using the NURSE mnemonic described in Table 17.

As challenging as it may be to implement new strategies to combat cancer misinformation, it is necessary if providers are to deliver appropriate, evidence-based treatment to their patients.

References

- 1. Kirkwood MK, Hanley A, Bruinooge SS, et al., The State of Oncology Practice in America, 2018: Results of the ASCO Practice Census Survey. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(7):e412-e420.

- 2. Chou, W-Y S, Gaysynsky A, Cappella JN. Where We Go From Here: Health Misinformation on Social Media. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(suppl 3): S273–S275.

- 3. Vosoughi S, Roy D, Aral S. The spread of true and false news online. Science. 2018;359(6380):1146-1151.

- 4. Johnson SB, Parsons M, Dorff T, et al. Cancer Misinformation and Harmful Information on Facebook and Other Social Media: A Brief Report. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021 July 22. (Epub ahead of print).

- 5. Johnson SB, Park HS, Gross CP, Yu JB. Use of alternative medicine for cancer and its impact on survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(1):121-124.

- 6. Johnson SB, Park HS, Gross CP, Yu JB. Complementary medicine, refusal of conventional cancer therapy, and survival among patients with curable cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(10):1375-1381.

- 7. Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5748-5752.