Historically, sexual minorities have been underserved in the healthcare setting. Members of this patient population may be less likely to receive optimal care, especially when it comes to preventive care such as lung cancer screening—a topic that was discussed during the Mini Oral Abstract Session “MA04: Health Policy and the Real World.”

The older (between ages 55 and 79) lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) population consists of approximately 400 million people in the United States and continues to grow. Studies show that the LGBT population tends to start using tobacco products at an early age and are less likely to have adequate access to medical care. Reasons for these trends vary; some patients may not seek routine medical care because of negative experiences with healthcare professionals, whereas other may have inadequate health insurance. With less routine care and cancer screening, this population is at higher risk for lung cancer or diagnosis at a later stage.

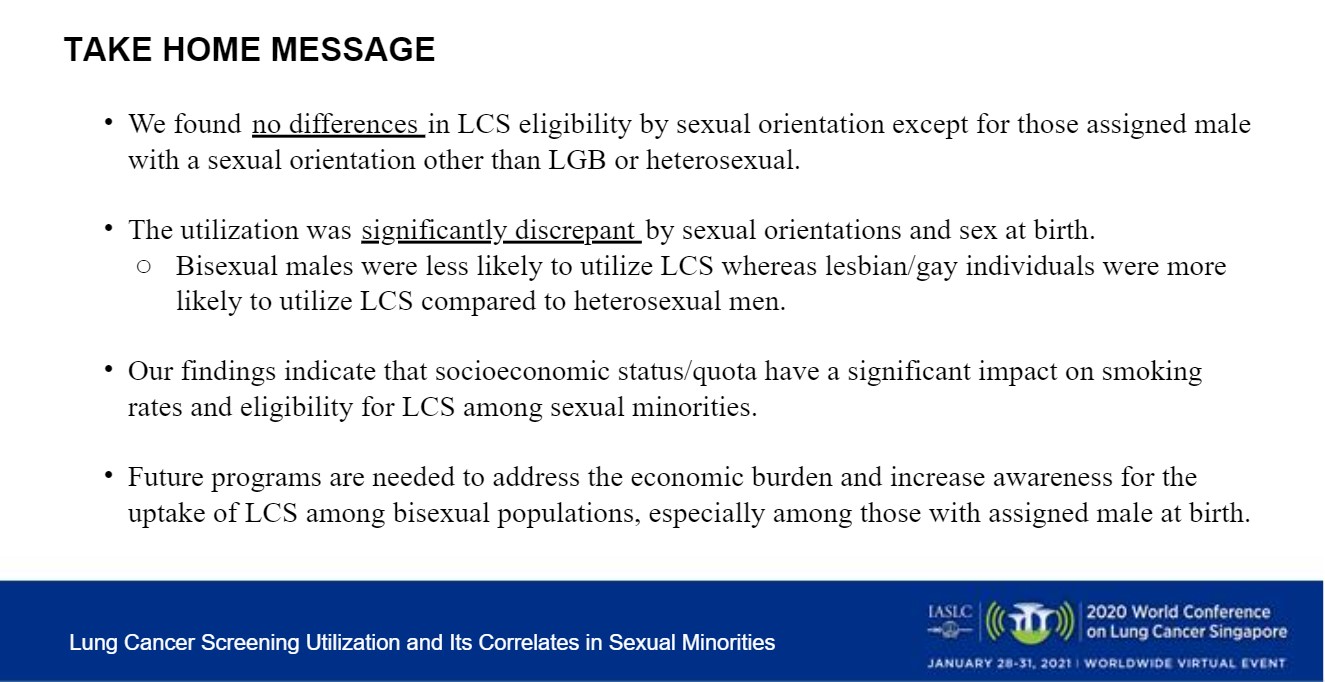

“It is important for healthcare providers and policy makers to be aware of the factors that are associated with lung cancer screening among the LGB population,” said Hui Xie, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Zilber School of Public Health. Dr. Xie’s presentation “Lung Cancer Screening Utilization and Its Correlates in Sexual Minorities: An Analysis of the BRFSS 2018,” discussed survey results that examined the social determinants regarding the receipt of lung cancer screening.

Dr. Xie’s research team looked at LCS as it correlates to sexual orientation, stratified by assigned sex at birth via the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of the 44,348 study participants, 1,439 self-identified as LGBT. Many (86.3%) had their last routine check-up more than 1 year ago. Most identified as straight, 1:00% identified as lesbian/gay, 0.56% identified as bisexual, and 0.25% identified as a different sexual minority not listed in the survey.

Of the study participants, 98.4% had health insurance, and 11.08% reported that they could not afford medical costs. Of those who participated in the survey, 84.53% identified as White, 6.00% as Black, 6.7% as Hispanic, 0.29% as Asian, and 2.49% identified with another race or ethnicity.

The goal was to determine the cause of the disparities among individuals in the LGBT population who receive screening for lung cancer compared with the rest of the population and, ideally, to close that gap. Eligibility criteria include people between the ages of 55 and 79 with no personal history of lung cancer who self-reported gender and sexual identity, and who had a history of smoking. Those who had a 30-year pack history but who had quit within the last 15 years were also included.

Study Results

Of the study participants, 14.37% were eligible for screening, and of those eligible, 22.85% were screened.

Among those assigned male sex at birth:

- Being gay or lesbian (OR: 5.30; 95% CI: 1.32-21.36; p = 0.019), having poor general health (OR: 4.16; 95% CI: 1.41-12.26; p = 0.010), and having no medical cost burden (OR: 9.37; 95% CI: 2.26-38.83; p = 0.002) were significantly associated with greater odds of receiving LCS.

- Being bisexual (OR: 0.13; 95% CI: 0.20-0.96; p = 0.045) and self-reporting as a heavy drinker (OR: 0.13; 95% CI: 0.02-0.75; p = 0.023) were associated with less likelihood of receiving screening.

Among those assigned female sex at birth:

- Poor general health (OR: 4.16; 95% CI: 1.41-12.26; p = 0.010) and have no medical cost burden (OR: 9.37; 95% CI: 2.26-38.83; p = 0.002) were significantly associated with greater odds of receiving LCS.

Bisexual individuals reported the highest smoking rate of 28.9%, which is doubled compared with heterosexual individuals (p < 0.0001).

Reducing Disparities

“Next steps could include the possible effect of intersectionality for the LGBT population — how the rate of lung cancer screening uptake may differ among sexual minorities by ethnicity, race, and geographic location,” Discussant Pamela Samson, MD, MPHS, of Washington University, St. Louis, said.

There are several ways to create a more comfortable experience for people who seek cancer screening:

- Ask what pronoun(s) the patient prefers,

- Use culturally inclusive intake forms,

- Not making assumptions based on appearance,

- Have gender-neutral bathrooms, and

- Hire staff at all levels who openly identify as LGBT.

Going forward, these studies will help healthcare providers identify and rectify barriers to cancer care and to explore approaches to better serve, and ideally, to improve quality of life for this community.