Editor’s Note: For more on clinical decision making in the era of neoadjuvant immunotherapy, read expert insights from Jamie E. Chaft, MD.

During the past ten years, great progress has been made in improving lung cancer survival. Early-stage, potentially curable lung cancers are being detected more frequently through targeted screening programs. Following on from successes in advanced disease, immunotherapy and EGFR-targeted therapy have now been shown to significantly improve survival in patients with operable lung cancer, as part of multimodality treatment. These treatment options are now approved in many countries.

However, the word ‘cure’ still needs to be used with caution. A recent surgical study of lobectomy versus segmentectomy in early stage 1B tumors (≤2 cm; IASLC staging 8th edition) reported a 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) of only 64% in both treatment arms.1 This was also noticeable in the ADAURA trial, which evaluated the addition of adjuvant osimertinib to surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with EGFR-mutated operable disease (tumor >3cms).2 The 2-year DFS in this study was 52% in the placebo arm, compared to 89% with the addition of adjuvant osimertinib. These data suggest that the outcomes for both EGFR and non-EGFR driven lung cancers are not as good as previously believed.

Multidisciplinary Decision Making

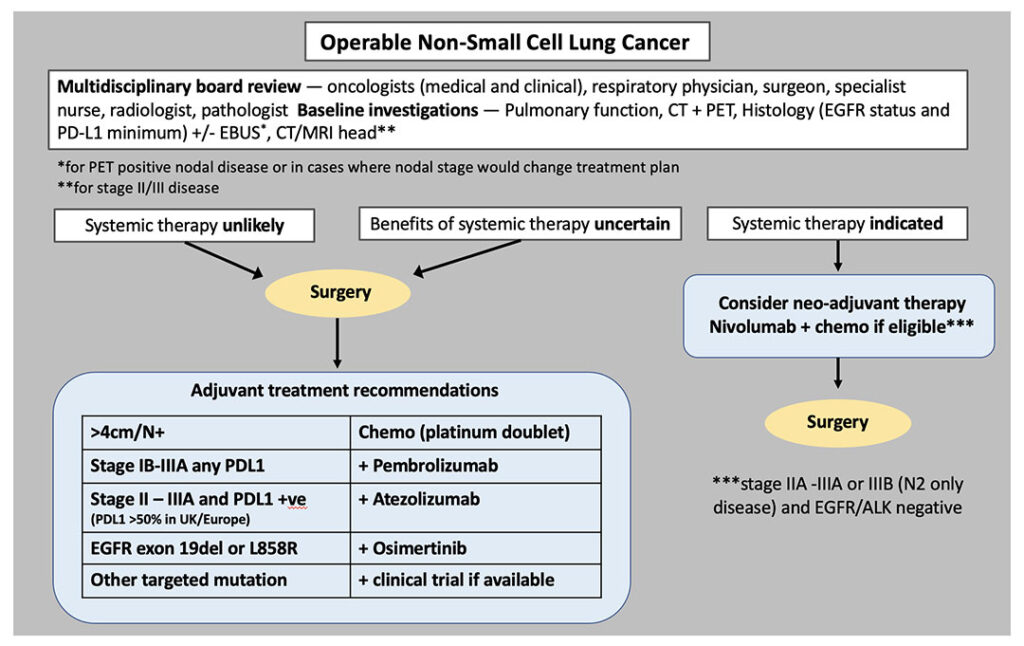

In this era of evolving neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment options, decision-making is becoming increasingly challenging. Accurate histological diagnosis, staging, and molecular profiling are essential to make appropriate treatment recommendations. At most centers, treatment decisions are made at tumor boards or multidisciplinary meetings. We will refer to these as multidisciplinary boards (MDBs) and propose discussion guidelines and a vision of how the latest radical lung cancer options can be incorporated into daily clinical practice (See Fig. 1).

Staging with a PET-CT scan and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) is currently used to identify patients who should have upfront surgery and those who will need systemic treatment. It is the latter group for whom a neoadjuvant/perioperative approach should be considered. There is also an intermediate group, where we would favor primary surgery to permit accurate surgical staging, inform prognosis, and guide decisions about adjuvant therapy.

Tumor size is an important point of discussion at an MDB, noting the difference between the licensing (or trial eligibility) for neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab (>4cms), adjuvant pembrolizumab (>4cms), adjuvant atezolizumab (>5cms) and neoadjuvant durvalumab (>5cms) in node negative populations.3

In addition, PD-L1 expression and EGFR mutation status are now essential for decision-making. Insufficient tissue for testing these two biomarkers—at a minimum—should trigger re-biopsy, EBUS, or may be an indication for definitive surgery before systemic treatment.

Patients with an EGFR-mutated tumor >4cm should be offered adjuvant chemotherapy followed by osimertinib, even when node negative (ADAURA), but tumors > 3cms could also be offered adjuvant osimertinib.2 This remains the best, evidence-based approach until data from the neoadjuvant osimertinib trial (NeoADAURA) are reported, and the license may be extended.4 Of note, patients with EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) only accounted for a small proportion of the total study population in recent adjuvant immunotherapy trials. Although there is no direct comparison of EGFR-targeted therapy versus immunotherapy, our experience in advanced disease has shown the limited efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with an EGFR mutation.5 We are therefore guided away from offering neoadjuvant or adjuvant immunotherapy to this group of patients.

Adjuvant Pembrolizumab or Atezolizumab?

PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 was an international, triple-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adjuvant pembrolizumab in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA NSCLC.6 The trial included all PD-L1 subgroups, and was positive for DFS with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.76. Notably, PD-L1 was not a predictive biomarker as benefit was seen in all PD-L1 subgroups, including PD-L1 <1%. On this basis, the FDA granted approval for pembrolizumab, irrespective of PD-L1 score.

The only subgroup that did not benefit from adjuvant pembrolizumab in PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 was the group that did not receive any adjuvant chemotherapy. Even patients who received one or two cycles experienced significant benefit from the addition of pembrolizumab. To date, this data on the use (or not) of chemotherapy is unique and is included as a prerequisite for the use of adjuvant pembrolizumab. The synergy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy is widely believed to result from cell death, antigen exposure, and disruption of immune evasion, albeit these are difficult to demonstrate in the adjuvant context.

The preceding IMpower010 trial also showed a significant DFS benefit of adjuvant atezolizumab in patients with stage II-IIIA, PD-L1 positive (>1%) disease (HR 0.66; 95% CI 0.50-0.88). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the benefit was predominantly generated by the PD-L1 >50% group (HR 0.43) rather than the PD-L1 1%-49% group (HR 0.87), and with no significant benefit seen for PD-L1 negative cancers (HR 0.97, CI 0.72-1.31).7 This resulted in FDA approval for PD-L1 positive cancers and with European approval restricted to patients with a PD-L1 score >50%.

Thus, we now have two active checkpoint inhibitors for use in the adjuvant setting after 1-4 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy. Although both immunotherapy agents are administered over one year, pembrolizumab is a 6-weekly regimen whereas atezolizumab is 4-weekly. PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 trial included smaller tumors (4-5cm even if node negative), while both drugs are approved for tumors ≥5 cms.

Take-Home Messages

- Initial surgery delivers tissue and staging data in a timely way. Adjuvant therapy based on these results is achieving excellent outcomes in all tumor groups.2,6,7

- A neoadjuvant approach can be considered for fit patients who will ultimately need systemic treatment. Currently this strategy will be time and resource saving compared to adjuvant therapies, however, we must bear in mind that there are a considerable number of patients who do not then reach surgery and a head-to-head comparison of neoadjuvant versus adjuvant is not available.

- Predictive biomarkers for MRD in all settings and pCR in the neoadjuvant setting are needed to optimize future perioperative treatment.

Adjuvant or Neoadjuvant?

In recent years, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been used for the treatment of less than 5% of stage II and III lung cancers,8 despite randomized data showing equivalence between neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy approaches.9

The CheckMate 816 study of neoadjuvant nivolumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy delivered impressive results in event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS). This study showed superiority of three cycles of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy compared to three cycles of chemotherapy alone.10 The pathological complete response (pCR) rate in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy was 24%, and it was these patients that drove the positive outcomes of the trial. Those who did not achieve pCR had similar outcomes with chemoimmunotherapy as patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone.

Although the short duration of this regimen is attractive, we must consider the substantial number of patients who did not undergo surgery (15.6% in the chemo-immunotherapy arm and 20% in the chemotherapy arm). Reasons provided included disease progression, unresectability, toxicity, patient refusal, or poor lung function.10 Careful selection of patients for a neoadjuvant approach is therefore crucial to avoid delaying potentially definitive surgery. Furthermore, we do not have a predictive biomarker to select patients who are most likely to achieve pCR with immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting.

CheckMate 816 was a pure neoadjuvant study, with no adjuvant treatment planned per protocol. So, the issue is not simply which adjuvant therapy should be offered, but whether short course neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy is equivalent—or superior—to longer course adjuvant therapy. It is important to note that the distribution of tumor stage differed within recent neoadjuvant and adjuvant trials. PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 and the IMpower010 trial were largely stage I-II weighted trials, while more than half of patients in CheckMate 816 had stage III disease.6,7,10 Therefore, as anticipated, there were more events reported for EFS in the CheckMate 816 study.

Other immunotherapy agents are now entering the neoadjuvant sphere in operable NSCLC. Data from the AEGEAN trial were recently presented at the American Association for Cancer Research annual meeting.3 AEGEAN was a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, trial evaluating neoadjuvant durvalumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy followed by one year of durvalumab in the post-operative setting. The pCR for the combination chemoimmunotherapy arm was 17.3% versus 4.3% for the chemotherapy alone arm. In this study, 20% of patients did not undergo surgery. Unlike CheckMate 816, AEGEAN was a much longer regimen, which incorporated both neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy.

Thus, adjuvant immunotherapy has found its place in lung cancer treatment and is a standard of care. Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy looks attractive when the treatment duration is shorter than adjuvant and the data appear equivalent. However, a head-to-head comparison has not been performed yet.

Future Directions

Oncology services are already hard pressed to maintain provision of care. At least 40% of advanced lung cancer patients receive up to two years of immunotherapy, not to mention those on maintenance pemetrexed and patients on long-term targeted therapy. There must be adequate capacity within services to promptly initiate neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy, closely monitor side effects during treatment and ensure that patients remain fit enough to proceed with surgery.

It is certain that further treatment options will emerge with ongoing trials. The NADIM-ADJUVANT trial will report this year. KEYNOTE-671 and the AEGEAN trial both included four cycles of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy followed by one year of adjuvant immunotherapy. The neoadjuvant-only approach from the short CheckMate 816 regimen may not remain the standard if the above trials report potential better outcomes.

There is still limited data on the optimal duration of immunotherapy in all disease settings. In early-stage disease, we must be mindful of ‘over-treatment’ when surgery alone may be curative. Systemic treatment, particularly immunotherapy, can have potentially life-long consequences for the patient and impact healthcare resources.

Biomarkers such as ctDNA could be used to evaluate minimal residual disease (MRD) post-surgery. The pCR rates in CheckMate 816 and AEGEAN are impressive and the development of predictive factors for pCR, which would enable us to select patients for a neoadjuvant strategy are needed. Longer term follow up will reveal how well this surrogate endpoint translates into an improvement in overall survival. In due course we will also discover whether MRD and/or pCR could guide de-escalation strategies and potentially spare patients unnecessary adjuvant treatment.

Adequate quantities of tissue from treatment-naïve tumors are required to personalize treatment options. This is particularly true with both new and active drugs to target EGFR and KRAS mutations, and ALK-MET translocations, to mention but a few. Oncogene addicted lung cancers are less likely to benefit from neo-adjuvant immunotherapy. In these patients, primary surgery followed by consideration of a clinical trial of adjuvant targeted therapies would be the preferred approach.

Conclusion

As the treatment landscape for operable early-stage lung cancer changes, decision making around operable cases is becoming increasingly complex. At the MDB, the oncologist has the ball in their court and can propose three cycles of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in patients with node-negative tumors >4cms, or node positive tumors deemed surgically resectable. While this has the potential to spare longer courses of adjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy, it will require a change in mindset among the MDB members making these decisions—as surgeons traditionally have liked to operate on fit patients without delay. Patients often also subscribe to this thought process, as is observed with the challenge of enrolling patients into trials of upfront surgery versus neoadjuvant treatment across cancer types. If the role of systemic therapy is considered borderline, for example in smaller node negative tumors, or if treatment tolerance to chemo-immunotherapy is a concern, we would recommend surgery followed by adjuvant therapy as informed by surgical staging.

However, we must bear in mind when recommending a neoadjuvant treatment that there are a considerable number of patients who do not reach surgery, and of those who do reach surgery, the benefit of additional post-surgical treatment is unknown until we have more details from trials with both a neoadjuvant and adjuvant approach. Ongoing trials may deliver important clinical and predictive biomarker data to further refine our decision-making in the future.

References

- 1. Altorki N, Wang X, Kozono D, et al. Lobar or Sublobar Resection for Peripheral Stage IA Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;388(6):489-498. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2212083

- 2. Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al. Osimertinib in Resected EGFR -Mutated Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer . New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(18):1711-1723. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2027071

- 3. Heymach JV et al. 2023 “Durvalumab-based Treatment Before and After Surgery Improved Outcomes for Patients With Resectable Non-small Cell Lung Cancer’. AACR Annual Meeting Orlando April 14-19 2023.

- 4. Tsuboi M, Weder W, Escriu C, et al. Neoadjuvant osimertinib with/without chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for EGFR-mutated resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: NeoADAURA. Future Oncology. 2021;17(31):4045-4055. doi:10.2217/fon-2021-0549

- 5. Lee CK, Man J, Lord S, et al. Checkpoint Inhibitors in Metastatic EGFR-Mutated Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer—A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2017;12(2):403-407. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.007

- 6. O’Brien M, Paz-Ares L, Marreaud S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB–IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2022;23(10):1274-1286. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00518-6

- 7. Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB–IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-1357. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02098-5

- 8. MacLean M, Luo X, Wang S, Kernstine K, Gerber DE, Xie Y. Outcomes of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in stage 2 and 3 non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of the National Cancer Database. Oncotarget. 2018;9(36):24470-24479. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.25327

- 9. Felip E, Rosell R, Maestre JA, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy plus surgery versus surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery alone in early-stage non – small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(19):3138-3145. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.6204

- 10. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;386(21):1973-1985. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2202170