Worldwide, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths. As in most of the world, lung cancer is a significant cause of cancer mortality in Latin America. The age-standardized 5-year survival rate in Brazil, for example, is 18%, which is concordant with global rates ranging from 10% to 20%.1 These low survival rates link directly with the diagnosis of most lung cancers at advanced stages.

Since the first publications of the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program in the 1990s, the superior effectiveness of computed tomography in detecting small pulmonary nodules compared to radiography has been demonstrated. Randomized studies—especially the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST)2 and NELSON—confirmed that it is possible to reduce mortality from lung cancer using low-dose radiation tomography.

During LALCA’s Lung Cancer Screening Session, which takes place from 17:00–18:00 today, January 25, I’ll be joined by Luis Corrales, MD, and Lucia Viola, MD, to discuss various screening-related challenges in Latin America.

Dr. Corrales, of Costa Rica’s Center for the Investigation and Management of Cancer (CIMCA), will begin with a lecture establishing lung cancer screening as the standard of care.

The NLST provided the first solid evidence that screening with low-dose CT (LDCT) can reduce lung cancer mortality risk in smokers who have smoked 30 pack-years or longer and in former smokers who have quit within the past 15 years. The study found that participants who underwent low-dose CT scans had a better chance of survival than participants who underwent standard chest X-rays.

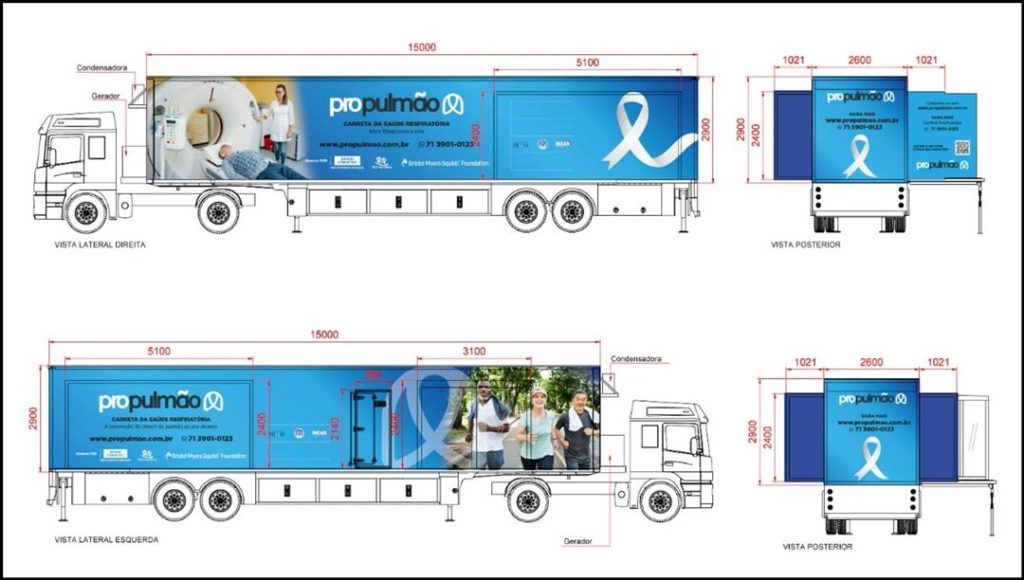

More recently, studies have focused on how to properly select candidates and implement lung cancer screening more comprehensively. During my presentation, I will discuss the various efforts under way in Brazil for this purpose, including a look at a mobile screening unit currently under construction for use in the northeast region of Brazil.

Since the publication of the NLST results, more has been learned about who may benefit the most from screening for lung cancer using LDCT. The NELSON trial conducted in Belgium and the Netherlands examined screening for lung cancer in smokers with CT, using a volume criterion for positivity, and found results consistent with the main NLST results, both in the impact on lung cancer mortality and in overdiagnosis.3

Data from the NLST, NELSON, and other smaller randomized trials are being regularly analyzed to examine other important issues in lung cancer screening, including cost-effectiveness, quality of life, and whether screening would benefit individuals younger than those enrolled in the NLST and those with fewer than 30 pack-years of smoking exposure.

Despite these results, lung cancer screening has not been established as a public health practice in developing countries such as Brazil, where there are high rates of granulomatous disease such as tuberculosis.

In this context, the Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT1) was conducted to address the effectiveness of screening in the country.4 Between January of 2013 and July of 2014, 790 participants volunteered to participate, following the same eligibility criteria employed in the NLST. The results of the baseline round of the Brazilian screening program showed that the prevalence of positive LDCT scans in Brazil was much higher than in other studies, including the NLST. However, current guidelines for managing nodules are still applicable and led to a similar prevalence of NSCLC (1.3%). Also, only 3.1% of the individuals screened required an invasive biopsy, again similar to other studies. This suggests that the prevalence of granulomatous disease did not elevate the number of false-positive results with a high suspicion for lung cancer, thereby avoiding unnecessary biopsy/operations.

More recently, BRELT2, a multicenter retrospective study, reported a similar prevalence of lung cancer compared to the single-institution BRELT1 study, raising great expectations for lung cancer screening programs in a country with a high incidence of granulomatous disease.5 Based on these recent studies, we demonstrated that it was possible to obtain the early diagnosis of lung cancer with low-dose tomography in different regions of Brazil. Despite the high incidence of tuberculosis, the analysis of pulmonary nodules by teams specialized in thoracic oncology allowed the safe investigation and diagnosis of lung cancer in numbers similar to those found in North America and Europe.

With this, we can encourage lung cancer screening throughout Latin America, where the epidemiological reality and available resources are similar to those found in Brazil.

While establishing the first lung cancer screening project in Brazil, which culminated in the publication of the BRELT1, we determined the execution of screening should include three phases, which we’ll review during the session.

- Community outreach where the main points of communication with the target population should be defined.

- Appropriate selection of candidates for screening, with the goal of reaching populations at higher risk for lung cancer.

- A multidisciplinary approach for reviewing all radiological findings where the best management for patients must be decided.

To expand the discussion, Dr. Lucia, of the Luis Carlos Sarmiento Angulo Cancer Treatment and Research Center, Bogota, Colombia, will share how incidental pulmonary nodule programs can complement lung cancer screening.

Though it is true that tobacco use remains the most substantial cause of lung cancer worldwide and primary prevention remains far more effective in reducing the incidence and mortality associated with lung cancer, efforts should still be made to start lung cancer screening programs and strengthen thoracic oncology programs based on the infrastructure already in place.

References

- 1. Babar L, Modi P, Anjum F. Lung Cancer Screening. [Updated 2022 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53728/

- 2. Pinsky PF, Church TR, Izmirlian G, et al.: The National Lung Screening Trial: results stratified by demographics, smoking history, and lung cancer histology. Cancer 119 (22): 3976-83, 2013.

- 3. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Heuvelmans MA, Lammers JJ, Weenink C, Yousaf-Khan U, Horeweg N, van ‘t Westeinde S, Prokop M, Mali WP, Mohamed Hoesein FAA, van Ooijen PMA, Aerts JGJV, den Bakker MA, Thunnissen E, Verschakelen J, Vliegenthart R, Walter JE, Ten Haaf K, Groen HJM, Oudkerk M. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 6;382(6):503-513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793. Epub 2020 Jan 29. PMID: 31995683.

- 4. dos Santos RS, Franceschini JP, Chate RC, Ghefter MC, Kay F, Trajano AL, Pereira JR, Succi JE, Fernando HC, Júnior RS. Do Current Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines Apply for Populations with High Prevalence of Granulomatous Disease? Results From the First Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT1). Ann Thorac Surg. 2016 Feb;101(2):481-6; discussion 487-8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.013. Epub 2015 Sep 26. PMID: 26409711.

- 5. Hochhegger B, Camargo S, da Silva Teles GB, Chate RC, Szarf G, Guimarães MD, Gross JL, Barbosa PNVP, Chiarantano RS, Reis RM, Mauad EC, Ghefter M, Sarmento P, Pereira R, Rocha J, Albuquerque ML, Miotto A, Almeida Dias DC, Franceschini JP, Fernando HC, Dos Santos RS. Challenges of Implementing Lung Cancer Screening in a Developing Country: Results of the Second Brazilian Early Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT2). JCO Glob Oncol. 2022 Jan;8:e2100257. doi: 10.1200/GO.21.00257. PMID: 35073147; PMCID: PMC8789215.