Mary Beth Beasley, MD

Precise pathologic staging of lung cancer resection specimens is a critical component of the post-operative treatment decision process, and information must be conveyed in the best possible fashion in the pathology report. While this may seem straightforward, studies scrutinizing pathology reports have found great variability in the completeness of information.1-3

In 2021, pathology reports were once again the focus of attention in a study published in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology by Smeltzer, et al. The study’s authors evaluated pathology reports from 11 institutions within their referral region based in Memphis, Tennessee, dividing them into reports from 2004-2009 and into four groups of reports from 2010-2020 that were subjected to various interventions. Interventions included education, synoptic reporting, addition of a lymph node kit or combinations thereof.

The researchers found improvement in reporting following interventions, particularly when all three were employed.4 The authors focused on what they determined to be the most essential items from the College of American Pathologists (CAP) lung cancer reporting protocol, namely specimen type, tumor size, histology, margin status, T category, and N category.

In particular, the inclusion of a synoptic reporting format, as encouraged by Smeltzer, et al, deserves some perspective. The CAP protocols were initially developed as a tool to “assist pathologists in providing clinically useful information as a result of the examination of surgical specimens” and the use of the protocols was voluntary.5,6

Following a recommendation by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (ACS-CoC), the CAP proceeded to produce more comprehensive checklists which include both “required” and “optional” elements. The current ACS standards stipulate that “90 percent of the eligible cancer pathology reports are structured using synoptic reporting format as defined by the College of American Pathologists cancer protocols, including containing all core data elements within the synoptic format.”7

It is important to note that, depending on the pathology practice situation, not all pathology labs are subject to ACS-CoC requirements, and not all laboratories elect to be accredited by CAP. However, standardization of pathology reporting has become a component of certain U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) payments related to quality measures.8 Additionally, for CAP accredited labs, while use of synoptic reporting was introduced in the inspection checklist in 2009, a lack of synoptic reporting was not considered an inspection deficit until 2015.9 Like them or hate them, the inclusion of synoptic reports has been shown to improve inclusion of necessary reporting elements.10,11 However, institution of a synoptic report is not as easy as it might seem.

In the interest of full disclosure, I have been a co-author of the CAP lung cancer reporting protocols since the 2009 edition, but will readily admit that, despite our best efforts, they are hardly perfect and contain elements that are ambiguous and/or subject to interpretation. Further, while the core elements emphasized by Smeltzer, et al, have remained the same, the protocols overall have become increasingly complex. Also, an often-overlooked factor is the degree of user-friendliness of the pathology laboratory information system (LIS).12,13

Electronic cancer checklists are frequently built into the LIS, but they are not uniform among systems, may be difficult to modify, and, as I discovered myself following an LIS upgrade, some elements that are required but “not applicable” to the specimen may not be transferred to the final report.

Smeltzer, et al, focus particularly on the accuracy of pathologic (p) T and N components. In regard to the accuracy of the pT component, it is unclear which standard the authors used to determine a discrepancy based on “independent assessment.” However, several issues pose challenges for the pathologist in regard to assigning an accurate pT designation.14,15 This is especially true in regard to adenocarcinomas with a lepidic component, in which the total tumor size and invasive tumor size must be recorded, but with the latter used to assign the pT using the current staging guidelines.16 Among other issues, such tumors may be difficult to accurately measure grossly as the lepidic component may be difficult to discern.

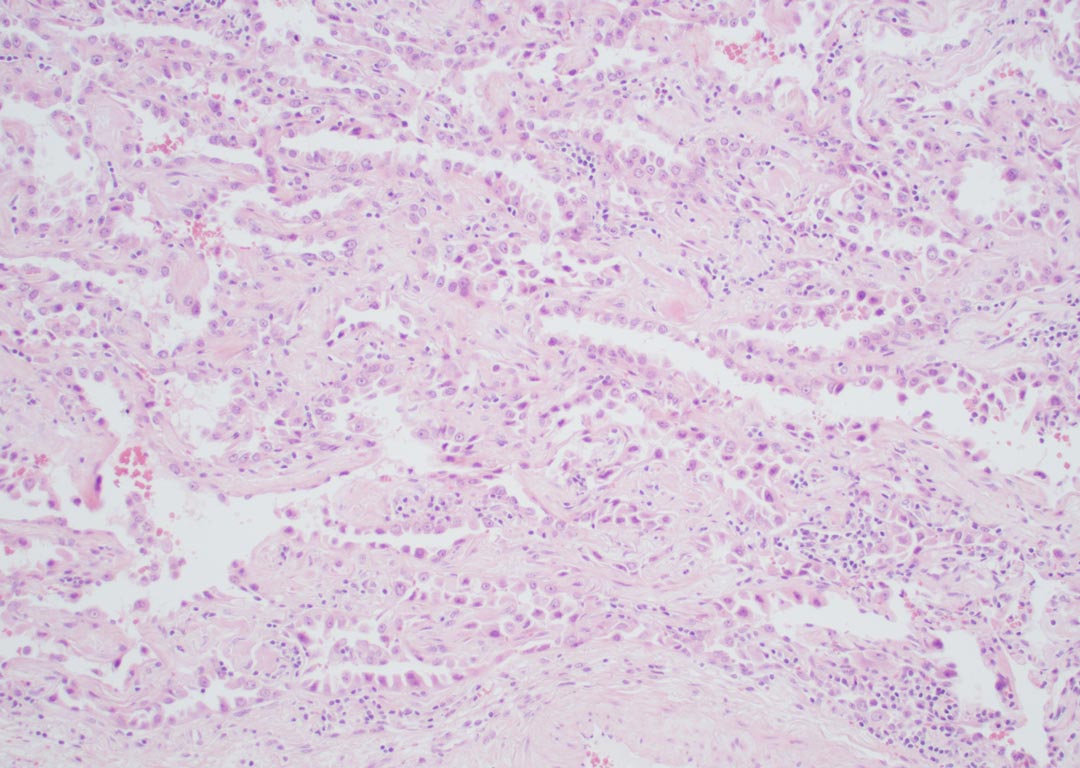

Example of an adenocarcinoma in which opinions may vary regarding whether there is lepidic growth, invasive growth, or both (hematoxylin and eosin stain 100x).

Critically, reproducibility of histologic patterns and, by extension, the invasive component is suboptimal, even among expert pathologists, and efforts by the IASLC pathology panel to identify areas for improvement are in progress.

Lymph node evaluation is another challenge. Many lung cancer resections do not include the recommended examination of nodal stations, and a significant number of resections have no nodes examined at all.17 From the pathologist’s perspective, it is important to point out that while lymph node dissections from lobectomy and pneumonectomy specimens are of variable quality, the analysis of N2 nodes is largely dependent on what the surgeon provides. Further, in the situation of a wedge resection, the nodes examined are essentially entirely dependent on the surgeon and not the pathologist.

Smeltzer, et al, comment that assignment of a pM component to the pathology report is “overwhelmingly disregarded” by pathologists in their system. Pathologists as a group tend to be conscientious, detail-oriented people, so it is my contention that incomplete reports are likely not the result of intentional disregard. For the record, an “M” designation is required only if confirmed pathologically,18 which is seldom applicable or known to the pathologist, as the authors note.

In my view, most of the reporting issues raised by Smeltzer, et al, and in similar articles can be improved by better communication among pathologists, surgeons, and other members of the clinical team. In the discussion, Smeltzer, et al, make the extremely important point that “improvement in pathologic staging quality requires intervention in the following three domains: events during the surgical operation, communication between surgical and pathology teams, and events during the pathologic evaluation of resection specimens.”

I would personally add a plea for accurate clinical history and radiographic information, but I otherwise think this is a conclusion everyone can agree with. William Osler once said, “As is your pathology, so is your medicine.”

Without question, pathology—and pathologic staging in particular—can be improved by multidisciplinary efforts.

References

- 1. Gephardt, G.N. & Baker, P.B. Lung carcinoma surgical pathology report adequacy: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of over 8300 cases from 464 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 120, 922-927 (1996).

- 2. Idowu, M.O., Bekeris, L.G., Raab, S., Ruby, S.G. & Nakhleh, R.E. Adequacy of surgical pathology reporting of cancer: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 86 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 134, 969-974 (2010).

- 3. Volmar, K.E. et al. Surgical pathology report defects: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 73 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 138, 602-612 (2014).

- 4. Smeltzer, M.P. et al. Trends in Accuracy and Comprehensiveness of Pathology Reports for Resected NSCLC in a High Mortality Area of the United States. J Thorac Oncol 16, 1663-1671 (2021).

- 5. Nash, G., Hutter, R.V. & Henson, D.E. Lung. In: College of American Pathologists (ed). Cancer Protocol Manual Ch. 1995, (2000).

- 6. Nash, G., Hutter, R.V. & Henson, D.E. Practice protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with lung cancer. Cancer Committee. Task Force on the Examination of Specimens from Patients with Lung Cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med 119, 695-700 (1995).

- 7. Commission on Cancer, American College of Surgeons: Optimal Resources for Cancer Care 2020 Standards (Updated Nov. 2021).

- 8. Hatfield, B.S. & Idowu, M.O. The Complete Surgical Pathology Report. In: R. E. Nakhleh & K. E. Volmar (eds). Error Reduction and Prevention in Surgical Pathology Ch. 11, (Springer, 2019).

- 9. College of American Pathologists. Personal communication (2022).

- 10. Aumann, K. et al. The format type has impact on the quality of pathology reports of oncological lung resection specimens. Lung Cancer 81, 382-387 (2013).

- 11. Sluijter, C.E., van Lonkhuijzen, L.R., van Slooten, H.J., Nagtegaal, I.D. & Overbeek, L.I. The effects of implementing synoptic pathology reporting in cancer diagnosis: a systematic review. Virchows Arch 468, 639-649 (2016).

- 12. Torous, V.F. et al. Exploring the College of American Pathologists Electronic Cancer Checklists: What They Are and What They Can Do for You. Arch Pathol Lab Med 145, 392-398 (2021).

- 13. Renshaw, A.A. & Gould, E.W. Exploring the College of American Pathologists Electronic Cancer Checklists: What They Are and What They Can Do for You. Arch Pathol Lab Med 146, 141a-141 (2022).

- 14. Renshaw, A.A. & Gould, E.W. Improving Reporting of Tumor Size in Synoptic Reports. Arch Pathol Lab Med 145, 969-972 (2021).

- 15. Butnor, K.J. & Beasley, M.B. Resolving dilemmas in lung cancer staging and histologic typing. Arch Pathol Lab Med 131, 1014-1015 (2007).

- 16. Staging Handbook in Thoracic Oncology. second edn, (IASLC: North Fort Myers, FL, 2016).

- 17. Osarogiagbon, R.U. et al. Outcomes After Use of a Lymph Node Collection Kit for Lung Cancer Surgery: A Pragmatic, Population-Based, Multi-Institutional, Staggered Implementation Study. J Thorac Oncol 16, 630-642 (2021).

- 18. Schneider, F., Beasley, M.B., Dacic, S. & Butnor, K.J. Protocol for the Examination of Resection Specimens from Patients with Primary Non-Small Cell Carcinoma, Small Cell Carcinoid or Carcinoid Tumor of the Lung. In: College of American Pathologists (ed). (2021).