In response to the steadily growing evidence of patient dissatisfaction, new medical school courses and educational techniques have evolved to teach patient–physician communication skills and their importance. However, the ability to embody an attitude of calm, compassion, and confidence may be more of a deeply ingrained personality trait than a reliably transferable skill set. Although not every physician was born to heal with a five-star bedside manner, all care providers can improve their communication skills and, by extension, their patients’ perceptions. And, in so doing, potentially enhance healthcare outcomes. Likewise, patients can take steps to ensure that their choices are known and reflected at each stage of care.

Communication Fundamentals for Trainees

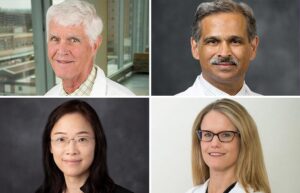

Pallavi Kumar, MD, is director of oncology palliative care and assistant professor of clinical medicine at Penn Medicine and teaches fellows and faculty optimal communication techniques. Communication skills were not always prioritized in medical schools, but Dr. Kumar is determined to give each of her trainees a proper appreciation of the power of patient–physician interactions, for better and for worse.

With medical trainees, Dr. Kumar works on communication fundamentals such as making eye contact and speaking clearly, as well as more complex but common tasks for palliative care and oncology physicians, like delivering serious news or responding to intense emotions.

“Doctors in both of these fields are very concerned with how we share information,” she said. “Whether it’s disease prognosis, treatment options, or how we guide people toward medical decisions in the context of their goals and values, all of this depends on good communication.”

Dr. Kumar explained that the traditional model has been doctors explain the disease and provide a menu of treatment options. That has changed, however, because “patients are looking to us for counsel, for recommendations on what they should do. As a result, we’ve changed how we view these conversations about tough medical decisions.”

Dr. Kumar’s general rule of thumb now is to talk less than half the time so that the patient can speak more.

“We need to listen to the patient’s goals, fears, and values and help them make healthcare decisions informed by that awareness,” she said. “Gone are the days when we said, ‘I’m the doctor and this is what you should do.’”

Likewise, it is hard for a patient to form a therapeutic bond with a doctor who is perceived as not understanding them or their disease.

“So number one,” Dr. Kumar advises students, “know the facts before you start talking.”

As discussed by Corey Langer, MD, in Part 1 of this series, timing is critical with these communications. When we’re dealing with a serious illness, Dr. Kumar said, clinicians should have these conversations well before a crisis situation and revisit the exchange if the clinical status changes.

“We need to ensure that goals and values stay properly aligned, because these things evolve over the course of an illness,” she said.

Also, loved ones should be involved early and often, and someone must be designated to act as the patient’s proxy, if the patient is incapacitated. Dr. Kumar recommends that patients choose a proxy who will not impose their own goals and values but will, rather, be a voice for the patient’s medical decision making.

Dr. Kumar noted that resources are available to help patients and their supporters get the most out of communication with care providers. One such resource is the Conversation Project, a public health initiative created at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“It’s a great online tool,” Dr. Kumar said. “It’s a conversation planning site that helps patients and families begin talking about what’s important to them and how to cope with potential healthcare scenarios.”

Dr. Kumar’s institution has also implemented the Serious Illness Care Program across all of its Abramson Cancer Center sites. The program trains all oncology clinicians to have goal- and value-based conversations with patients using a structured conversation guide.

Ultimately for Dr. Kumar, a prime indicator of success in patient–physician communication comes not from her patients, but from their families.

“Although many of our seriously ill patients ultimately die from their disease, the best-case scenario is when bereaved family members look back and agree that we followed their loved one’s goals and wishes. That is a really important outcome—hard to measure, but very important,” she said.

Palliative Care Skills Training

Alana Sagin, MD, specializes in hospice and palliative care and serves as Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine at Penn. She provides an extra layer of patient communication support, symptom management, and help addressing caregiver needs. She also heads up medical-student education in palliative care at the Penn School of Medicine.

Dr. Sagin told ILCN that she and her colleagues have started working on a four-year comprehensive curriculum on palliative care that will cover a number of topics, including pain and symptom reduction, dealing with one’s own emotions when treating patients with serious illness, advanced palliative care understanding, and patient–physician communication. The program is still catching up to ensure every medical student gets this communication skills training, but the goal is complete training and broad application.

“There are good data now to show that high-quality communication skills training for medical trainees can improve the quality of care, as well as the patient and family experiences, and decrease medical provider burnout,” Dr. Sagin said. “In these situations, patients are going through incredibly difficult and emotional times in their lives. We need to be the best communicators possible to help them feel supported and cope with what they are facing.”

Sometimes over the course of an illness, tensions can rise and it may seem as if medical providers and family members are at odds with each other. Dr. Sagin advises a collective discussion in these situations.

“Give them that space and the back and forth with you, and you’ll see the tensions begin to melt, and everybody feels much better. Everyone feels like they are on the same page, even if no decisions are made at that time,” she said. “So much distress can be alleviated this way. I see it time and time again.”

Dr. Sagin said another thing to remember for trainee physicians is that even long-time practitioners should be continually improving their communication skills.

“It is a lifelong process, and not something where you can graduate medical school having perfected it,” she said. “It’s something we always need to be striving to improve.”